Diogene di Sinope, meglio conosciuto come il Cinico, è certamente una delle figure più eccentriche e iconoclastiche della filosofia antica. Nato intorno al 412 a.C. a Sinope, città greca sul Mar Nero, fu discepolo di Antistene, il fondatore della scuola cinica. La filosofia cinica, che Diogene incarnò con estrema dedizione, si fonda su una critica radicale della società e dei suoi valori, favorendo, invece, la semplicità, l’autosufficienza e la virtù come unica vera ricchezza.

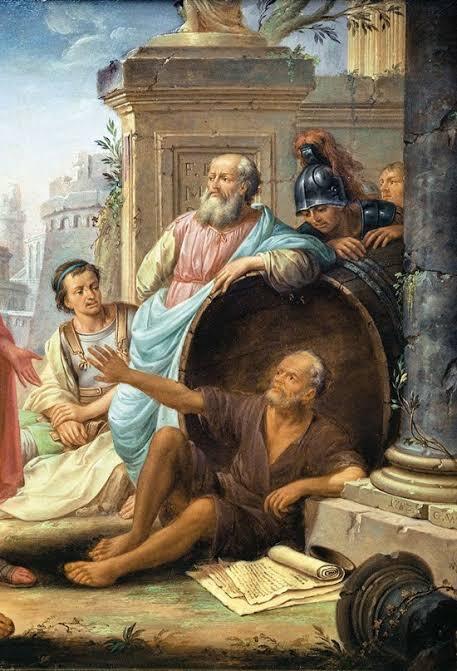

Diogene è famoso per la sua vita austera e per i molti aneddoti che lo vedono protagonista, spesso con intenti provocatori. Si dice che vivesse in una botte, rifiutando qualsiasi tipo di comodità materiale. Una delle storie più celebri narra dell’incontro con Alessandro Magno. Quando il re macedone, incuriosito dalla fama del filosofo, gli chiese se potesse fare qualcosa per lui, Diogene rispose semplicemente: “Sì, scansati, perché mi stai togliendo il sole”. Questa risposta incarna perfettamente l’atteggiamento cinico di Diogene verso il potere e la ricchezza, considerati irrilevanti rispetto alla libertà e alla felicità derivanti dall’autosufficienza.

La filosofia di Diogene si basa su pochi principi cardine, che mettono in discussione i valori convenzionali della società.

Credeva che la vera felicità fosse raggiungibile solo attraverso l’autosufficienza. Rifiutava il superfluo e viveva con il minimo indispensabile, dimostrando che la felicità non dipende dalle ricchezze materiali. Sfidava apertamente le norme e le convenzioni sociali. Per lui, le leggi e i costumi erano spesso artifici inutili che distoglievano gli individui dalla ricerca della vera virtù.

Seguendo la lezione di Socrate, considerava la virtù come l’unica vera ricchezza. Per lui, vivere secondo natura e in armonia con essa era l’obiettivo principale dell’esistenza.

Diogene praticava e promuoveva la parresia, la franchezza radicale nel dire la verità. Questo atteggiamento lo portava spesso a scontrarsi con le autorità e con i benpensanti del suo tempo.

Diogene è ricordato non solo per la sua vita ascetica e i suoi comportamenti provocatori, ma anche per l’impatto duraturo delle sue idee. La sua critica della società e delle sue ipocrisie ha influenzato molte correnti filosofiche successive, tra cui lo stoicismo. Inoltre, la sua figura continua a essere un simbolo di ribellione contro l’ingiustizia e l’irrazionalità, ispirando artisti, pensatori e ribelli di ogni epoca.

Diogene, quindi, non è solo un personaggio storico, ma un emblema della ricerca della verità e della virtù contro le convenzioni e le illusioni del mondo. La sua vita e la sua filosofia invitano a riflettere su ciò che veramente conta e su come si possa vivere in maniera più autentica e significativa.