These my brand-new reflections on geopolitics present it as a philosophical field, emphasizing the influence of geography on political strategies and the impact of geopolitical actions on collective identities and human conditions. It integrates classical philosophical thoughts on power and State acts, aiming to deepen the understanding of nations’ strategic behaviours and ethical considerations. This reflective approach seeks to enhance insights into global interactions and the shaping of geopolitical landscapes.

The Geo-Philosophy

Part III

Geophilosophy means first and foremost what its name suggests: geo-philosophy, philosophy of the earth. However, the sense of the genitive, which, as is well known, can be understood in a dual sense, remains unprejudiced. In a subjective sense, the expression “philosophy of the earth” is philosophically banal, as it refers to cosmology if by “earth” we mean the orb, or to natural philosophy or Physics if by “earth” we mean the phýsei onta, the beings that come from Phýsis and that are therefore determined by kínesis, or “motility,” or even to anthropology if by “earth” we mean that sector of being that constitutes the subordinate complement of the sphere of transcendence: ethics as the determination of the good, aesthetics as the determination of the beautiful, law as the determination of the just, and politics as the determination of the good life.

In an objective sense, “philosophy of the earth” can still mean two things:

the earth of philosophy, in an emphatic sense, that is, the homeland, or, as is said today under the influence of a great and controversial master like Heidegger, the Heimat, the native place or womb from which thought is placed or re-placed in the world;

or the being delivered (of thought) to the earth, the absolute terrestriality of thought, its prison, to put it with Nietzsche—if we rightly understand his appeal to fidelity to the earth—, and thus again anthropology, but in a very different sense from the one previously mentioned.

Taken in the objective sense, the expression “philosophy of the earth” can thus mean either a reference to the transcendence of being, which would be the true homeland-motherland of thought (thought is of being, it belongs to it, it is it that places it in the world), or a reference to a plane of “absolute immanence,” on which the human and the historical find consistency but where there is no longer any trace of Man or of History, in which the celestial is contemplated, but only as a possible dimension of an absolute terrestrial, the theological problem is admitted but only as a problem internal to the horizon of an absolute anthropological. Such a thought more than ascertains the fall of man into a closed system; it expresses it, is, so to speak, the symptomatic manifestation of it.

Taken in the objective sense, the expression “philosophy of the earth” thus refers to two irreconcilable things, of which only one is geophilosophy in the sense mentioned above, that is, a thought of local instances, a “Lutheran” use of the mind, and a thought of immanence. Every other meaning of the term refers instead, always anew, to the philosophical primacy of theology.

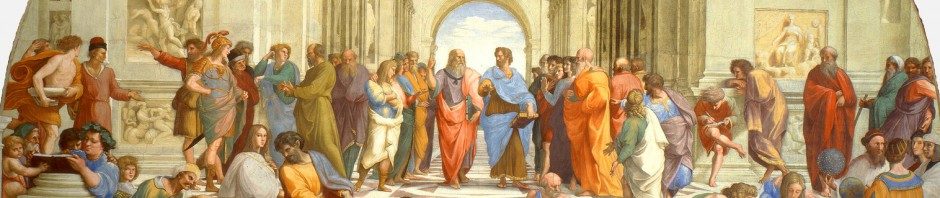

In general, philosophy is precisely the attempt to assume the earth in the cone of light of an “elevated” and “eternal” gaze capable of embracing everything with a single glance (Plato: synoptikós), or of thinking the whole or the conditions of possibility of the whole (Kant) and thus reflecting its elements and articulations in relation to God or its secularized substitute, the subject, who of God, as Deleuze wrote, conserves precisely the essential: the place. The metric of philosophizing therefore admits, as its only dimension, the verticality; its presupposition is that the whole is transparent in all senses; its perfection is theology; its movement a movement of seesawing between up and down: 1. elevatory perspective, aimed at comprehending all differences and their relationships; 2. descensio ordinatoria, tending to organize and distribute as much meaning as possible.

To make this step, to discover this path between the cracks and in the dysfunction of the Western project, is not, however, professional philosophy, but rather the instances that were traditionally excluded: feminine domestic thoughtfulness, the somber provincial disposition to obsessive fantasies. These instances, emancipated by the expansive movement of the West (urbanized, technologized, acculturated, deprovincialized), suddenly restored as much to the freedom of thought as to the truth of their origins, suffer here an essential shock: faced with the discovery of being nothing other than the silent reserve of the homogeneous world, of the legal and thought community, seized at the edges of historical existence, the primary gesture with which they make their entrance onto the undifferentiated plane of the human is a gesture of refusal or, to be more precise, of withdrawal, of flight toward the thicket. Such “withdrawal” is akin to what Jünger called “passing into the woods,” but it is also an ascent toward the dawn of civilization, toward the prehistoric point at which separation and exclusion have not yet occurred, toward that zero degree of the West in which thought, springing forth, can be founded only on the absence of authority and is therefore, to put it with Bataille, a sovereign gesture, toward the point at which events, occurring, show their radical gratuitousness and in which the state is present rather as pure and simple par-oikía, a system of neighborhood, a form of condominium: neither peace nor war it might be said, mere coexistence—after all, it must be considered that peace is a pure fiction, as it can occur only as the nullification of conflict, brutal subjugation, or annihilation of the enemy as enemy. Such “withdrawal” expresses the refusal to assimilate to the productive homogeneity of the philosophy of the State and the estrangement with respect to its system of legitimation, the derision of its pedagogical function, and the horror for its professionalism. It is for this reason that geophilosophy, at the exact point where it flows, presents itself with the features of a wild thought, not conforming to the educational standards of public philosophy and thus as an uneducated, non-orthopedicized, implausible thought, to which, by definition, the consent of the scientific community cannot go—and therefore also a thought “false” or a false thought and, finally, as an illegal thought, disrespectful of the protocols and legality of scientific practices. Its methodological approach will appear rather as brigandage—this is the meaning to be attributed to the expression “Lutheranism of the mind,” at least from the perspective of homogeneous philosophy: it involves the exercise of something like a “free examination” conducted on texts that the philosophical church transmits, in a sacralizing manner, within a consolidated magisterium; free examination that, in the most extreme situations, may also appear as wild textualism or a sort of methodological vampirism.

Geophilosophy as such arises from a withdrawal of thought, from a wilding, from an attempt to gain not an elevated point of view, but a point of departure as external, lateral, and foreign to the procedures of homogeneous thought as possible. This at least is its public image, its cultural image. From the “geo-” perspective, what here appears as an ensemble of implausible forms presents itself instead now as a fight against culture, now as a revolt against politics, now as a movement of secretion, disappearance, and impulse to autonomy, now as a victimizing philosophy (the assumption of the viewpoint of the victim and the criminal instead of that of the community and the state—the geophilosophy indicates, moreover, an absolute victim, a paradigm of victim: the ἱδιότηϛ, the excluded from common thought, but also the being that stands alone, the private, the domestic, the paysan, the woman, the excluded from the political community and finally the excluded from the historical community, that is, the being without past and future).