The investiture controversy stemmed from two opposing ideologies: the imperial and the ecclesiastical. Under Constantine (313), the Church was elevated to the highest social and imperial dignity but was simultaneously integrated into the administrative and legal structure of the empire. From Charlemagne onward, the Church became an integral part of the empire, realizing Augustine’s dream of the “Regnum Dei” on earth. However, this integration rendered the Church subservient to the emperor, particularly under the Ottonian and German Henry rulers, who turned it into a vital instrument and foundation of imperial power. In serving the emperor, the Church betrayed its primary and intimate vocation and mission, which came from God. The Church’s moral stature was further degraded by struggles for the papacy, simony, and Nicolaism, all compounded by imperial theocracy, an untenable situation. Overturning this institutionalized reality, both de jure and de facto, was extremely challenging, as it required a transformation of the spiritual and moral climate that shaped the era’s culture and conscience. A decisive impetus came with the foundation of the Abbey of Cluny (910), which established over two thousand monasteries directly under the abbot of Cluny and thus the pope, removing them from imperial control. The most evident manifestation of the Church’s subordination to the Empire was ecclesiastical investitures, which were taken from the Church and given to the emperor, serving his needs. The conflict over this critical issue reached its peak between Henry IV and Gregory VII (1073–1085). Gregory VII’s “Dictatus Papae” not only outlined the future and independent papacy but reversed the roles, shifting from imperial theocracy to pronounced ecclesiastical hierocracy. Canon XII stated, “To him (the pope) is granted the right to depose the emperor,” and Canon XXVII declared, “He (the pope) can release subjects from their oath of loyalty in cases of wrongdoing.” Having established the theological and legal foundations for the separation of Church and Empire, it was now necessary to implement them in practice. The opportunity arose when Henry IV appointed several bishops. Gregory VII refused to recognize these appointments. In response, Henry convened the Synod of Worms (1076) and deposed the pope, who retaliated by excommunicating the emperor. This forced Henry IV to do penance at Canossa. Through this act of apparent submission, Henry IV regained imperial legitimacy and presented himself as a “rex iustus,” turning apparent defeat into a political victory. However, after being excommunicated again, Henry succeeded in deposing Gregory VII, who died in exile in 1085. Despite this apparent victory, the Church’s reformist faction persisted. The pope elected by the emperor, Clement III (1084), was not recognized, and Urban II was chosen instead, following the brief pontificate of Victor III. Urban II resumed Gregorian reforms, and Henry IV was eventually deposed by his son, Henry V. The latter concluded an agreement with Paschal II, whereby the emperor renounced election rights, and bishops relinquished their estates. However, the agreement failed due to strong opposition from the bishops, who feared impoverishment. Success came with the Concordat of Worms (September 23, 1122) between Callistus II and Henry V: the pope retained the right to appointments, while the emperor was granted regalian rights. The Concordat was significant for formalizing the separation of powers and responsibilities, but it was also a compromise. Through imperial regalia, bishops remained tied to the emperor by an oath of loyalty. By then, other kingdoms, such as France and England, had reached agreements with the Church, renouncing ecclesiastical investitures in exchange for oaths of allegiance. However, the issue was more complex in Germany, where investitures involved sovereign rights that could not simply be transferred to the Church. Ultimately, as mentioned earlier, the matter was resolved with the Concordat of Worms. This act harmonized imperial law with the Church’s growing authority. The Concordat was further ratified by the Diet of Bamberg and the First Lateran Council (1123).

Effects of the Concordat of Worms on the “Ecclesia Universalis”

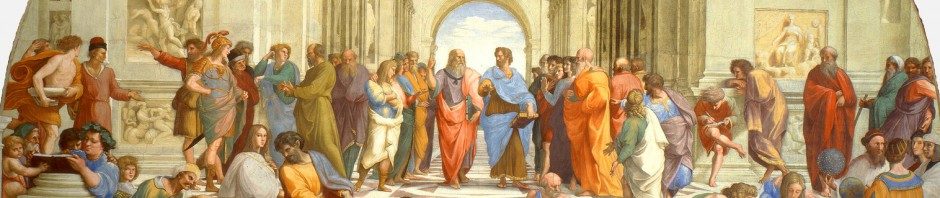

The Concordat of Worms granted the Church direct authority over ecclesiastical appointments, concentrating the clergy and Christendom around the pope, who became the central figure of Western Christianity. While the Church achieved greater autonomy and internal cohesion, the West had yet to reach a clear ontological distinction between Church and State, persisting in the unity of Priesthood and Kingdom. In this complex framework, rulers, now stripped of ecclesiastical power, were relegated to the status of “laymen” and, as such, became subject to the Church’s sovereignty. The Church increasingly asserted its spiritual authority throughout Christendom, transforming into a universal Church with the priesthood as the guiding force of the Christian West. This marked a shift from imperial theocracy to ecclesiastical hierocracy. Consequently, the Church experienced a paradox: internal unity centered on the papacy and a growing division between ecclesiastical and secular domains. In the 12th and 13th centuries, the distinction between Priesthood and Kingdom became more pronounced, with Christendom coalescing around the pope, who gained increased authority in both ecclesiastical and temporal matters. The pope embodied the unity of the Christian West, grounded in a single faith and culture.

Competences of the Papacy After the Concordat of Worms

Following the Gregorian Reforms, the imperial theocratic axis shifted to an ecclesiastical hierocratic one. The papacy, now the leader of Christendom, extended its competences beyond ecclesiastical matters to temporal ones. In ecclesiastical affairs, the pope was the apex of the priesthood and the visible principle of Christian unity. In temporal matters, as the vicar of Christ, the pope wielded equal importance, reigning as sovereign over the Papal States and feudal vassal states. He conferred imperial crowns and exercised extensive authority over temporal powers. Thus, the temporal was subordinate to the spiritual, with the State serving as the Church’s secular arm while maintaining autonomy. This relationship was likened to “soul and body” or “sun and moon.” The Crusades and campaigns against heretics exemplified this new State-Church relationship.

The Papacy After the Concordat of Worms

The Concordat of Worms sought to resolve the issue of investitures by promoting a dual system: the king granted temporal investiture, symbolized by the scepter, while the Church retained the right to ecclesiastical election and appointment, symbolized by the ring and crozier. The Concordat addressed the investiture conflict but not the broader relationship between Church and State. The Church retained its feudal structure throughout the Middle Ages, while the Gregorian Reforms initially equated spiritual and temporal powers before asserting the superiority of the spiritual. This dynamic reached its peak under Innocent III (1198–1216), who epitomized the Church’s spiritual and temporal authority. The conflict between Frederick Barbarossa and Alexander III (1159–1181) underscored these tensions, culminating in the Peace of Venice (1177). The Third Lateran Council (1179) established a two-thirds majority rule for papal elections. At the heart of this power struggle lay two ideas: Christ as the sovereign of Christendom; the dual power symbolized by two swords, one temporal (the emperor’s) and one spiritual (the pope’s), with the Church retaining ultimate authority over both. This concept dominated Church-State relations, reaching its zenith under Innocent III.

Institutional Consolidation and Recognition

The Gregorian Reforms and the Concordat of Worms marked a turning point in the Church’s autonomy, freeing it from imperial control over internal governance. The Church consolidated internally, creating an efficient bureaucratic apparatus led by the College of Cardinals, which shared responsibilities with the pope. Innocent III exemplified the medieval papacy’s power and prestige, fulfilling Gregory VII’s vision of the Church as the pinnacle of Western Christendom’s spiritual and political authority. However, this dominance was short-lived due to the modest capabilities of his successors and resistance from figures like Frederick II, who rejected such a concept of the Church.