The Causes of the Separation

Various factors contributed to the birth of the Middle Ages, among which the alliance between the Church and the barbarian populations played a significant role. This was encouraged by the gradual separation of Rome from Constantinople during the 8th century.

The slow and progressive detachment between East and West has its roots as early as the 5th century.

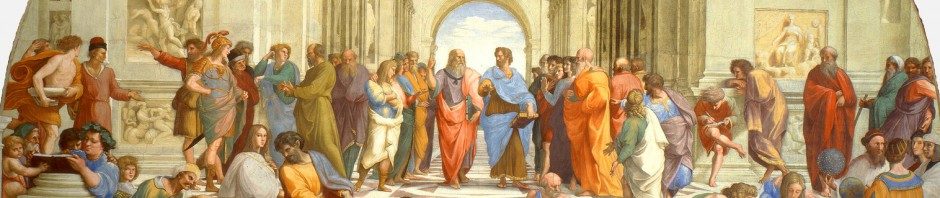

Until 397, the year of St. Ambrose’s death, the Church was uniform throughout the Roman Empire, which acted as a unifying force. However, by the 5th century, strong tensions began to arise between the churches of the Eastern and Western regions. The factors that favoured the separation between the East and the West were essentially three:

- Linguistic divergence: Greek, the official language of the Church, was replaced by Latin. The Western Church began to ignore Greek, introducing Latin within its practices. In this regard, Pope Damasus (380) introduced Latin into the Western liturgy and entrusted St. Jerome with the translation of the Septuagint from Greek into Latin, which resulted in the creation of the “Vulgate.” This language shift altered the way things were understood and communicated, leading to a change in culture and perspective. Thus, the East remained Byzantine, while the West became Latin.

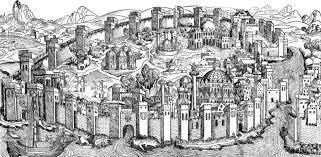

- Political fracture: The Western Roman Empire quickly collapsed under the pressure of barbarian invasions, while the Eastern Roman Empire lasted until the 15th century, ending with the fall of Constantinople (1453) to the Arabs. Additionally, there developed a strong Western aversion toward the East, which, in an effort to alleviate the pressure from the barbarians, granted them settlements in the West, which the East regarded as barbarized and culturally inferior.

- Different ecclesiastical structures: On May 11, 330, Emperor Constantine moved the imperial seat from Rome to Constantinople, the new Rome. In the West, this created a political and administrative void that the Church slowly and tacitly filled, becoming the natural heir to the former Western Empire, which had been effectively abandoned by the emperor. Consequently, Rome, along with the West, believed it could operate independently, effectively abandoning the Eastern Emperor and his Empire.

Additionally, differing views on the Church separated the East from the West:

- In the East, the structure was quadripatriarchal (Antioch, Alexandria, Constantinople, Jerusalem), with Rome as the fifth patriarchate.

- Moreover, for the East, decisions were to be made communally and with mutual agreement. It was thus inconceivable that Rome alone would decide for and over everyone. Consequently, the East developed a communal approach, while the West adopted a monarchical one.

Beyond all else, the general atmosphere had changed: the East, by nature, was contemplative, while the West had a practical and concrete view of things. This different mindset was reflected in the respective liturgies: those of the East were elaborate and rich in symbolism, while those of the West were sober and practical.

These various sources of friction between East and West manifested as early as the 5th century in two ruptures in relations: the first lasting 11 years (404–415), the second lasting 50 years (484–534), the latter caused by the issuance of Zeno’s Henotikon (482), which sought to resolve Christological disputes between the Monophysites and Dyophysites following the Council of Chalcedon (451).

From the 5th century onward, the East and the West followed paths that increasingly alienated them from each other, particularly regarding the Monophysite and Dyophysite issues left unresolved by Chalcedon, from which emerged Monothelitism and Monoenergism. The East, in particular, struggled to reconcile the supreme purity of God with the fallen nature of humanity. This Monothelite controversy was addressed at the Council in Trullo I (680), restoring relations between the two Churches.

However, this fragile peace was disrupted by Justinian II (685–695), who sought to interfere in the internal affairs of the Church concerning ecclesiastical discipline. To this end, he convened a council, the Council in Trullo II, in 692 without consulting Pope Sergius I (687–701). This council, intended by the emperor to complete the work of the two previous councils—namely, the Fifth (Second Council of Constantinople in 553) and the Sixth (Third Council of Constantinople in 680), also known as Trullo I—came to be known as the Quinisext Council. Of the 102 canons approved, many were in open conflict with Western Church customs, and as a result, Pope Sergius I refused to sign them, rejecting even the copy reserved for him, despite intense imperial pressure. An agreement on these canons was reached only with Pope Constantine I (708–715), who accepted only about fifty of them after traveling to Constantinople, where the privileges of the Roman Church were renewed.

New Controversies: Leo III and Popes Gregory II and Gregory III

After the resolution of the 102 canons from the Council in Trullo II or Quinisext (692), peace between the state and the Church was again disrupted by two disputes between Emperor Leo III and Popes Gregory II (715–731) and Gregory III (731–741).

Upon ascending the throne, Leo III had to engage in significant military efforts to defeat the Arabs and quell the rebellion in Sicily. These wars drained the imperial treasury, prompting Leo III to impose heavy taxes on the Roman Church, thereby violating its privileges. Gregory II firmly opposed these imperial abuses, regarding them as a grave offense to the Western Church. Leo III, in turn, interpreted the papal refusal as an act of rebellion, which he sought to suppress, though unsuccessfully, due to a popular uprising and the unexpected support of the Lombards for the pope

The Iconoclastic controversy

Another point of conflict between the Empire and the Papacy was the iconoclastic controversy, which unfolded in two phases and lasted about a century.

The first phase (726–787) began with Leo III’s order to destroy the images in Constantinople and persecute the monks who guarded them. It was during this phase that John of Damascus intervened, introducing the distinction between adoration and veneration.

The iconoclastic movement was condemned by the Roman Church, and relations with Constantinople worsened when Leo III, as part of an imperial reorganization, significantly reduced the territorial jurisdiction of the Roman Patriarchate in favour of that of Constantinople. Rome lost control of Southern Italy, Sicily, Greece, Macedonia, and the Balkan Peninsula. The conflict continued with Leo III’s son, Constantine V, who persisted in the fight against images, developing a theological justification for iconoclasm.

The situation was resolved at the Second Council of Nicaea (787), convened by Empress Irene in agreement with Pope Adrian (772–795), although the council was not approved by the Synod of Frankfurt, convened by Charlemagne, who had been excluded from the conciliar decision-making process due to a misunderstanding.

The Second Phase (814–843)

The second phase of the iconoclastic controversy occurred under Leo V, who launched a new offensive against the veneration of images, attributing the Empire’s poor state to the relaxation of the struggle against images. Empress Theodora, like Irene, convened a new council in 843, which restored the veneration of images and established the Feast of the Triumph of Orthodoxy, still celebrated today on the first Sunday of Lent.

The Motivations of Iconoclasm

The motivations behind iconoclasm were rooted not only in Exodus 20:4 and Deuteronomy 4:15, which prohibit the worship of images, but also in Jewish and Islamic cultures, which viewed images as a violation of God’s transcendence, asserting that He cannot be represented. Additionally, early Church tradition was opposed to images, and bishops feared a return to idolatry and paganism.

These reasons found theological support at the Council of Hieria (754).

Opposing the iconoclast position, John of Damascus emphasized the important distinction between “adoration,” reserved for God alone, and “veneration,” due only to the saints.

It was also highlighted that, through the Incarnation, God Himself took on the image of man, and thus, humanity is permitted to use images in worship, which, far from containing or representing divinity, instead point toward it.