The strong missionary drive led by the Anglo-Saxons and St. Boniface (Winfrid), coupled with the establishment of the Papal State, had concentrated significant power in the hands of the Pope, extending across almost the entire Western world.

Following the death of Pope Adrian I (772-795), Leo III (795-816), a presbyter of humble origins, ascended to the papacy. However, he soon became embroiled in courtly intrigues, facing accusations of perjury and adultery, which led to his arrest.

Leo III managed to escape and sought refuge with Charlemagne, who travelled to Rome in November 800 to resolve the papal controversy and restore order. A synod convened to examine the accusations against the Pope, but it declared itself unable to judge, invoking the principle of “Prima sedes a nemine iudicatur,” derived from a false document known as the Symmachian (from Pope Symmachus, 498-514). This forgery created an account of an invented Council of Sinuessa in 303 that asserted this principle.

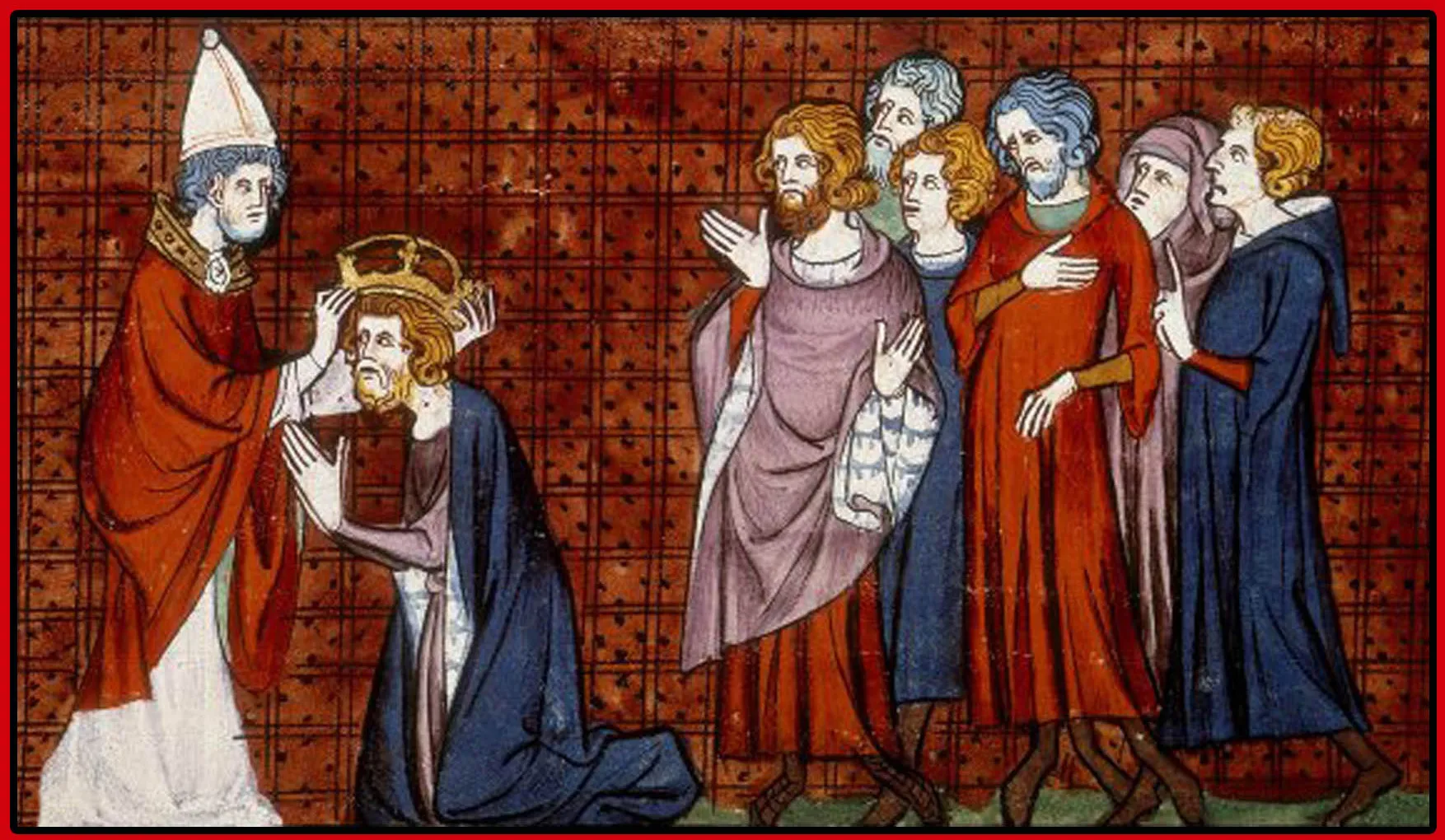

Two days after the Roman synod concluded on December 23, 800, Charlemagne was acclaimed and crowned emperor in a ceremony modelled after the Byzantine imperial coronation. Although the event appeared sudden and unexpected, various signs indicate that the coronation was prearranged: the elaborate imperial welcome Charlemagne received upon his arrival in Rome, where an opulent crown was already prepared. Additionally, there had been previous imperial aspirations advocating for equal status between Charlemagne and the Byzantine Emperor.

It is likely that this plan was agreed upon between Pope Leo III (795-816) and Charlemagne during their meeting in Paderborn.

The coronation marked a definitive break between Rome and Constantinople and initiated a new era in Christendom, characterized by dual leadership: the Pope and the Emperor. It also represented a turning point in Church-Empire relations, establishing the anointing, coronation, and papal consecration as essential elements of imperial authority.

Charlemagne and the establishment of the Holy Roman Empire

The rise of Charlemagne (768-814) and his subsequent coronation solidified the idea of a restored Roman Empire. He strengthened his internal power and expanded his influence outward. The coronation on December 25, 800, as “Imperator Romanorum,” definitively asserted his dominance over the West. This title was later formally recognized by Byzantium through a series of agreements.

For Charlemagne, however, titles held less significance than the essence of imperial authority, free from Roman claims. He envisioned a new “Imperium Romanum” akin to the Byzantine model, centralized in the core of the Carolingian realm along the Meuse and Rhine.

Thus, two years after his coronation, Charlemagne required an oath of allegiance and sought formal acknowledgment of his title from Constantinople, which Byzantium granted through agreements concluded between 810 and 814. This recognition marked Byzantium’s permanent retreat from Western affairs.

Following these agreements, Charlemagne crowned his son Louis the Pious in Aachen in 813, using the Byzantine imperial rite. This coronation was reiterated in 816 at Reims by Pope Stephen V, reinforcing the Roman origin of the imperial title, which was in service to the Church’s protection.

Charlemagne diligently worked to create a cohesive empire: he mandated the use of a standardized script (Carolingian minuscule); aligned Latin with patristic standards; imposed a unified liturgy blending Gallican-Frankish and Roman traditions; and standardized monastic practices under the Rule of St. Benedict.

Despite these efforts, the Empire remained fragile due to Charlemagne’s death in 814, which prevented full consolidation. The Frankish inheritance system, which called for power-sharing among heirs, also contributed to its downfall.

After Charlemagne’s death, the Holy Roman Empire was divided into three separate kingdoms. Louis the Pious, Charlemagne’s successor, distributed the Empire among his sons according to Frankish succession customs, formalized by the Treaty of Verdun (843), which permanently divided the Empire and ended the unity of the Western Holy Roman Empire. This fragmentation led to significant internal and external pressures, culminating in the abdication of Charles the Fat, one of Charlemagne’s descendants, who proved unable to defend the Empire. The realm ultimately split into five distinct entities: Germany, France, Italy, and Upper and Lower Burgundy, with the imperial title ceasing upon the death of Berengar I, who was assassinated in Verona in 924.

The decline of the Empire coincided with the Church’s waning influence.

In Italy, the papacy, bolstered by the “Pactum Ludovicianum,” secured its autonomy, severing ties with the decaying Carolingian Empire. While this newfound autonomy could have been advantageous, it sparked fierce power struggles. The papacy became a highly contested institution among Roman nobility and southern Italian leaders, resulting in violent conflicts. This era, known as the “Saeculum Obscurum” of the Church, saw rapid turnovers in the papal office, often driven by the shifting dominance of competing factions, leading to instances where rival popes were simultaneously appointed.

A reflection on Theocracy in the Carolingian Empire

It is essential to differentiate between the terms “theocracy,” “hierocracy,” and “caesaropapism.”

“Theocracy” refers to the intervention of rulers in religious matters that fall within the Church’s jurisdiction. In contrast, “hierocracy” is the Church’s intrusion into State affairs. “Caesaropapism” denotes the State’s involvement in the internal administration and organization of the Church.

The Carolingian era was marked by theocratic tendencies, particularly evident in liturgical reform, which aligned with Roman practices yet incorporated local elements, resulting in the Franco-Roman liturgy. This reform was initiated by rulers, not the Church. This development would later give rise to the Latin liturgy.

In legal matters, the “Dionysio-Hadriana Collection” was upheld, augmented with new legislation to meet evolving needs.

Episcopal offices were integrated into the Kingdom through feudal rights.

Legislative mechanisms in the Carolingian period included:

- Mixed councils, comprising both clerical and lay participants, tasked with legislating social and ecclesiastical matters.

- The Capitularies, or laws supplementing ordinary chapters.

- The Missi dominici, inspectors sent on missions throughout the Empire, composed of bishops and lay officials. This overview highlights how, in Carolingian governance, religious and secular responsibilities were interwoven. Charlemagne also engaged in theological debates, such as Adoptionism, which claimed Jesus was God’s Son by adoption; and Iconoclasm, initially resolved by the Second Council of Nicaea convened by Empress Irene but whose conclusions Charlemagne rejected due to the exclusion of the Frankish Church. This applied similarly to the Filioque dispute, stemming from the Council of Constantinople (381).

Charlemagne played a significant role in these matters, but unlike Byzantine emperors, he respected papal authority, maintaining a clear distinction between religious and state powers within the Empire’s unified administration, thus permitting ecclesiastical autonomy.

Two principal powers emerged, mutually independent yet interlinked: religious and secular. This concept, clearly expressed by Pope Gelasius (492-496) in a letter to Emperor Anastasius in 494 and influencing Western political thought for over a millennium, identified the Church with the broader world. The Church was perceived not as an intermediary between God and humanity but as a “Societas fidelium,” where every member, according to their role, was committed to defending the Kingdom of God and converting all people to God. This universalistic view led the Church to embody “Ecclesia universalis.” The ancient Church’s Christ Pantocrator, creator of all, took on an earthly aspect in the medieval period: Christ became the supreme Priest and King governing the “Ecclesia universalis,” encompassing all Christian humanity. Here, the Pope and the King represented sacramental counterparts of one reality: Christ, who lived and expressed Himself through them.

Yet, by the 8th century, a gradual separation between the laity and priesthood began to emerge, initially evident in the liturgy, which symbolized the Church’s life. The King, as a consecrated layman, retained a sacred status, thereby serving as Christ’s legitimate earthly representative.