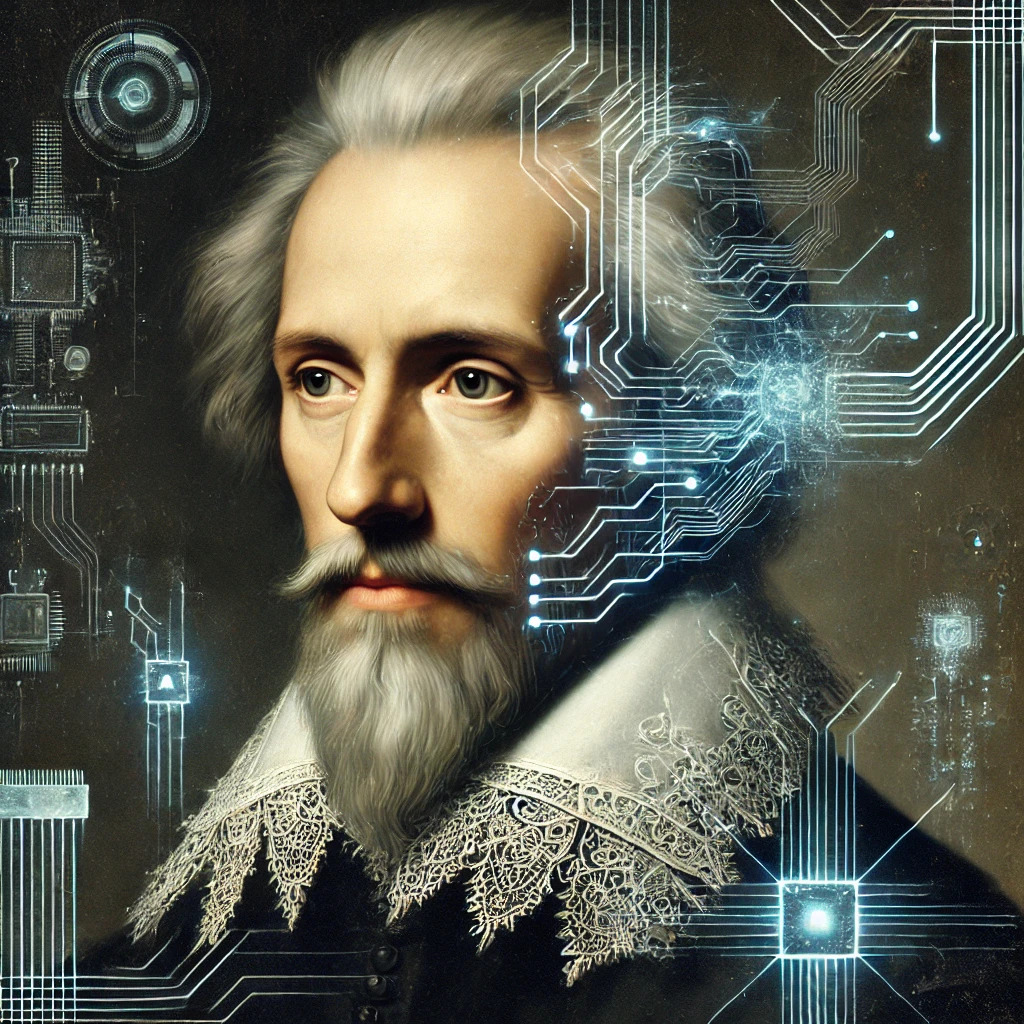

De iure belli ac pacis (Sul diritto della guerra e della pace), pubblicato nel 1625, è l’opera più celebre del giurista e filosofo olandese Ugo Grozio (Hugo de Groot). Questo trattato ha segnato un punto di svolta nella storia del pensiero giuridico e politico, ponendo le basi teoriche per il diritto internazionale moderno. In un’epoca segnata da guerre feroci, instabilità politica e conflitti religiosi – in particolare la Guerra dei Trent’anni – Grozio propose un sistema di norme giuridiche valide anche in tempo di guerra, cercando di umanizzare i conflitti e limitare la violenza tra Stati.

Grozio scriveva in un momento in cui l’Europa era lacerata da conflitti politici e religiosi che mettevano in discussione l’unità del diritto e dell’autorità. La frattura tra cattolici e protestanti, la crisi dell’autorità imperiale e l’affermazione degli Stati sovrani rendevano urgente la necessità di un ordine giuridico nuovo, capace di trascendere le divisioni confessionali e garantire una convivenza pacifica.

Inoltre, l’emergere del concetto di Stato moderno e il declino dell’autorità papale e imperiale spingevano i pensatori a interrogarsi su cosa potesse regolare i rapporti tra entità politiche indipendenti. Grozio rispose a questa domanda costruendo un sistema giuridico fondato sulla ragione naturale, ossia su princìpi che tutti gli uomini potessero riconoscere indipendentemente dalla religione o dalla cultura.

De iure belli ac pacis è diviso in tre libri. Nel Libro I – “Fondamenti del diritto naturale e del diritto delle genti”, Grozio principiò da una riflessione teorica sul diritto naturale: esiste un ordine di giustizia universale, comprensibile attraverso la ragione, che precede e fonda il diritto positivo (cioè il diritto creato dagli uomini). In una delle sue affermazioni più celebri, sostenne: “Ci sarebbe diritto anche se si concedesse – cosa che non si può fare senza empietà – che Dio non esista”. Con questa frase, Grozio affermò la piena autonomia del diritto naturale dalla religione: la legge morale non ha bisogno della rivelazione divina per essere valida. Questo è un passaggio cruciale verso una concezione laica e razionale del diritto. Inoltre, in questo libro, Grozio distinse tra ius naturale (diritto naturale) e ius gentium (diritto delle genti), cioè quell’insieme di norme che regolano i rapporti tra le nazioni. Nel Libro II – “Le cause giuste della guerra”, analizzò in quali casi una guerra potesse essere considerata giusta. La guerra, per essere legittima, deve avere uno scopo giuridicamente fondato: difesa da un’aggressione, punizione di un torto subito, recupero di un diritto violato. Grozio condannava le guerre di conquista e le guerre preventive non fondate su una minaccia reale. Per lui, la sovranità non giustifica automaticamente la guerra: anche i sovrani devono sottostare a regole. Questa è una netta presa di distanza dal realismo politico di autori come Machiavelli o Hobbes. Nel Libro III – “Il diritto nella guerra (ius in bello)” affrontò il comportamento lecito durante i conflitti. Anche quando una guerra è giusta, ci sono limiti da rispettare. Non tutto è permesso: devono essere tutelati i civili, i prigionieri e deve essere evitata la crudeltà gratuita. L’intento è chiaramente quello di “civilizzare” la guerra, ponendo limiti morali e giuridici alla violenza. In questo senso, anticipò molti dei princìpi che si sarebbero ritrovati nel diritto internazionale umanitario contemporaneo, come le Convenzioni di Ginevra.

L’impatto dell’opera di Grozio è stato duraturo. Il suo pensiero ha influenzato filosofi, giuristi e teorici della politica nei secoli successivi, da Pufendorf a Kant, da Locke a Vattel. La sua visione di un ordine giuridico internazionale fondato sulla ragione ha anticipato l’idea di una comunità delle nazioni regolata da norme condivise, che si sarebbe ritorvata nei progetti dell’Illuminismo e, più tardi, nelle istituzioni moderne come l’ONU o la Corte Internazionale di Giustizia.

Grozio è spesso definito il “padre del diritto internazionale” proprio perché ha posto le basi teoriche di un diritto che non si limita ai confini degli Stati, ma regola i rapporti tra di essi in nome di una razionalità giuridica superiore.

De iure belli ac pacis fu un tentativo coraggioso e innovativo di costruire un diritto comune in un’epoca di disordine. Grozio si rivolse alla ragione come fondamento della convivenza tra gli uomini e tra gli Stati, superando il particolarismo delle leggi nazionali e l’arbitrarietà del potere. In un mondo in cui la guerra sembrava inevitabile e spesso giustificata da pretesti religiosi o politici, Grozio ebbe l’ambizione – e la lucidità – di immaginare un sistema giuridico universale, in cui anche il conflitto fosse soggetto a regole. La sua lezione rimane attuale: in un’epoca globale segnata da nuove tensioni e minacce, il richiamo alla ragione e alla legge come strumenti per contenere la violenza e garantire la pace non ha perso forza.

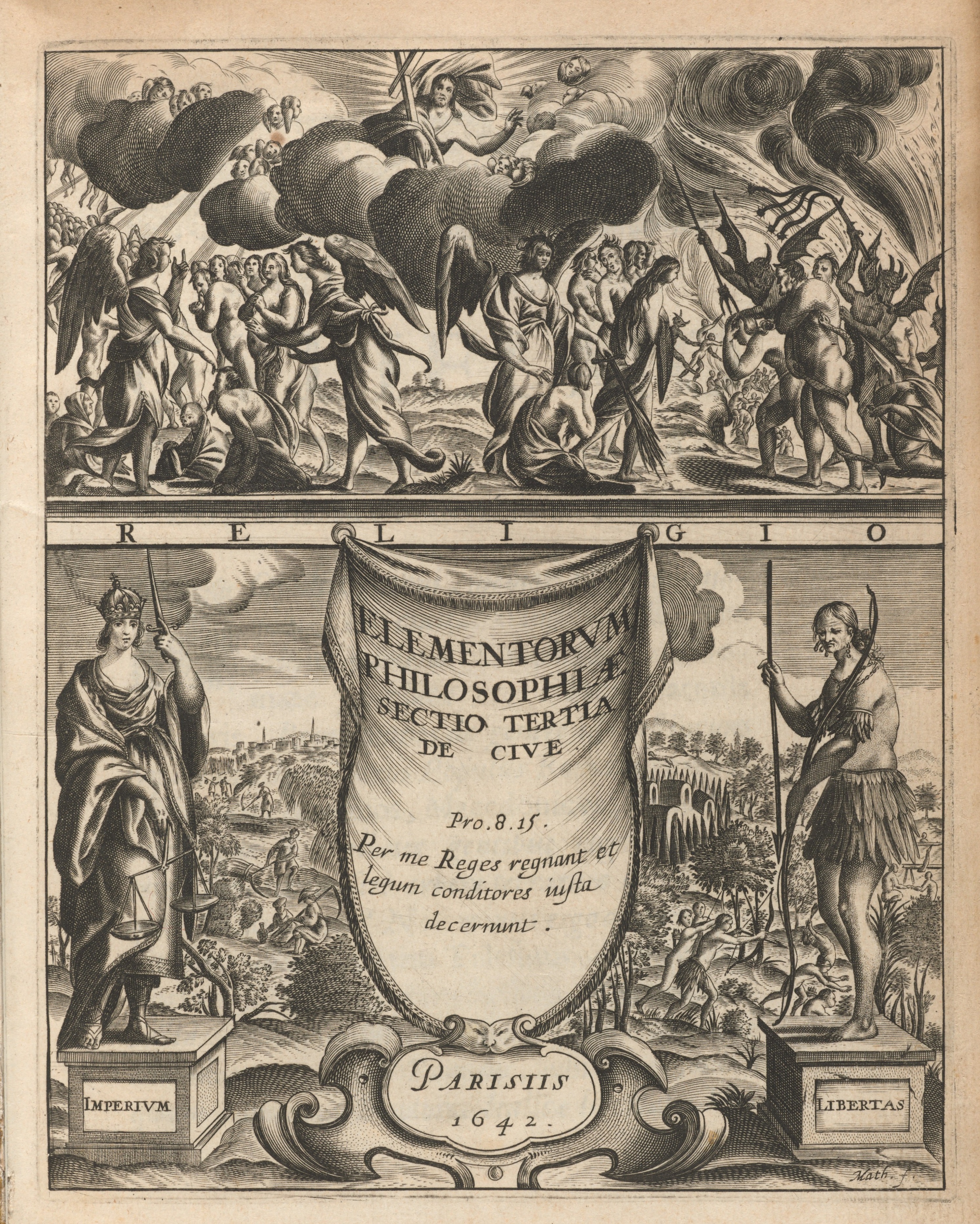

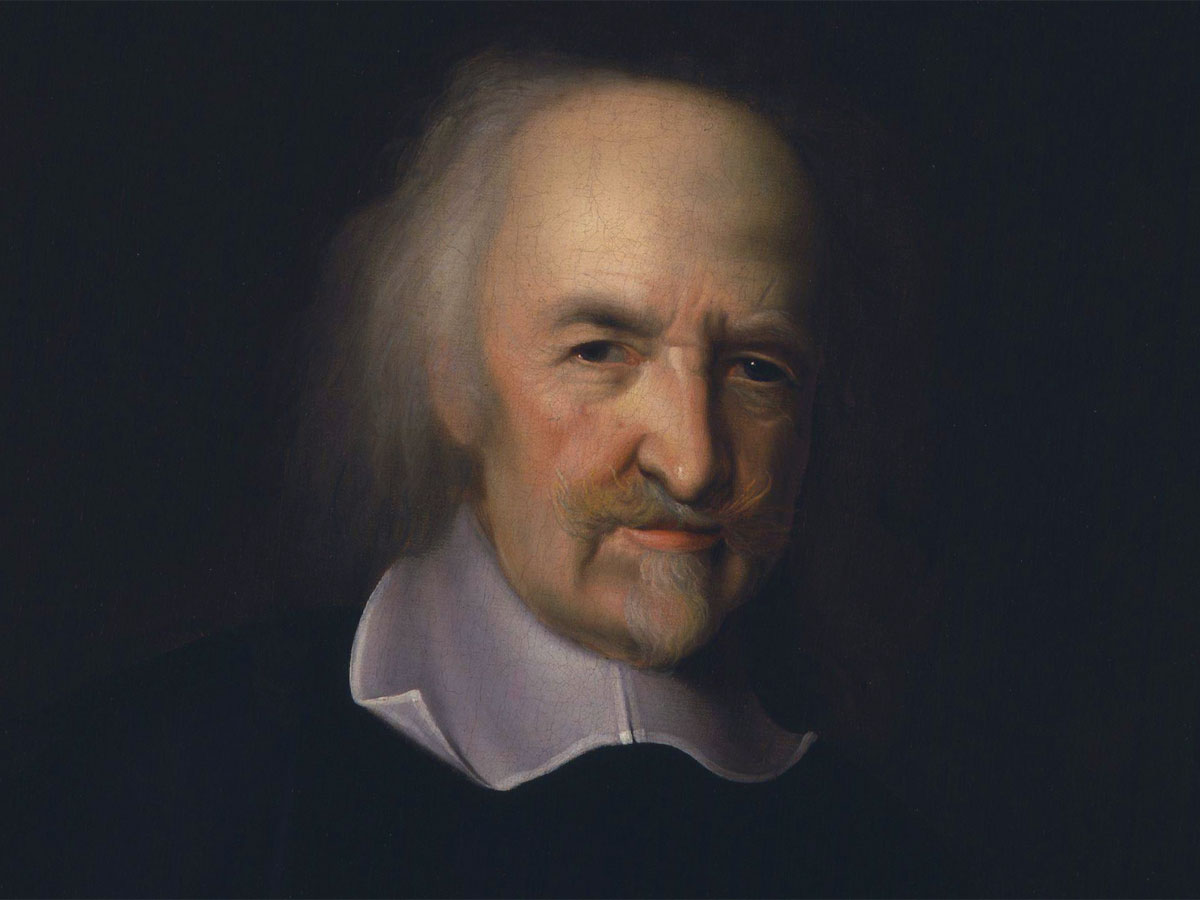

La caratteristica distintiva dell’AI rispetto al Leviatano di Hobbes risiede nella sua decentralizzazione. Mentre il Leviatano è rappresentato come un’entità singola e sovrana, che detiene tutto il potere, l’autorità dell’AI è distribuita attraverso una rete di attori. Questa rete include governi, aziende tecnologiche e sviluppatori indipendenti, che detengono diverse forme di potere regolatorio. Il controllo dell’AI, dunque, non è concentrato in un’unica figura sovrana, ma frammentato e diffuso attraverso un complesso sistema di governance algoritmica. Questo cambia radicalmente il modo in cui dobbiamo pensare al potere nell’era digitale.

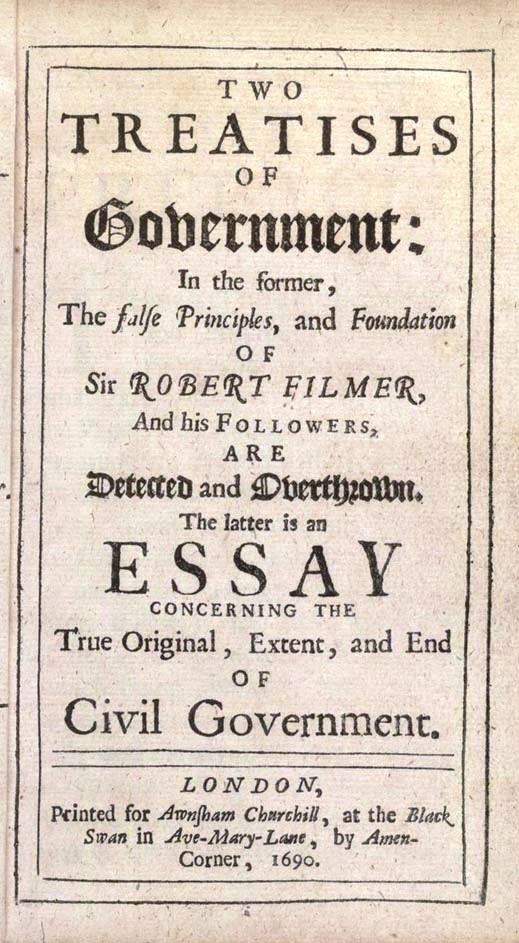

La caratteristica distintiva dell’AI rispetto al Leviatano di Hobbes risiede nella sua decentralizzazione. Mentre il Leviatano è rappresentato come un’entità singola e sovrana, che detiene tutto il potere, l’autorità dell’AI è distribuita attraverso una rete di attori. Questa rete include governi, aziende tecnologiche e sviluppatori indipendenti, che detengono diverse forme di potere regolatorio. Il controllo dell’AI, dunque, non è concentrato in un’unica figura sovrana, ma frammentato e diffuso attraverso un complesso sistema di governance algoritmica. Questo cambia radicalmente il modo in cui dobbiamo pensare al potere nell’era digitale. Nel magnum opus Due trattati sul governo, pubblicata anonima nel 1690, John Locke tesse una tela intricata e raffinata di idee, che hanno plasmato i fondamenti del pensiero liberale moderno. Quest’opera non è un semplice trattato politico, ma attraversa l’essenza stessa della libertà e della legittimità politica, un inno ai diritti innati dell’individuo e alla sovranità del popolo.

Nel magnum opus Due trattati sul governo, pubblicata anonima nel 1690, John Locke tesse una tela intricata e raffinata di idee, che hanno plasmato i fondamenti del pensiero liberale moderno. Quest’opera non è un semplice trattato politico, ma attraversa l’essenza stessa della libertà e della legittimità politica, un inno ai diritti innati dell’individuo e alla sovranità del popolo.