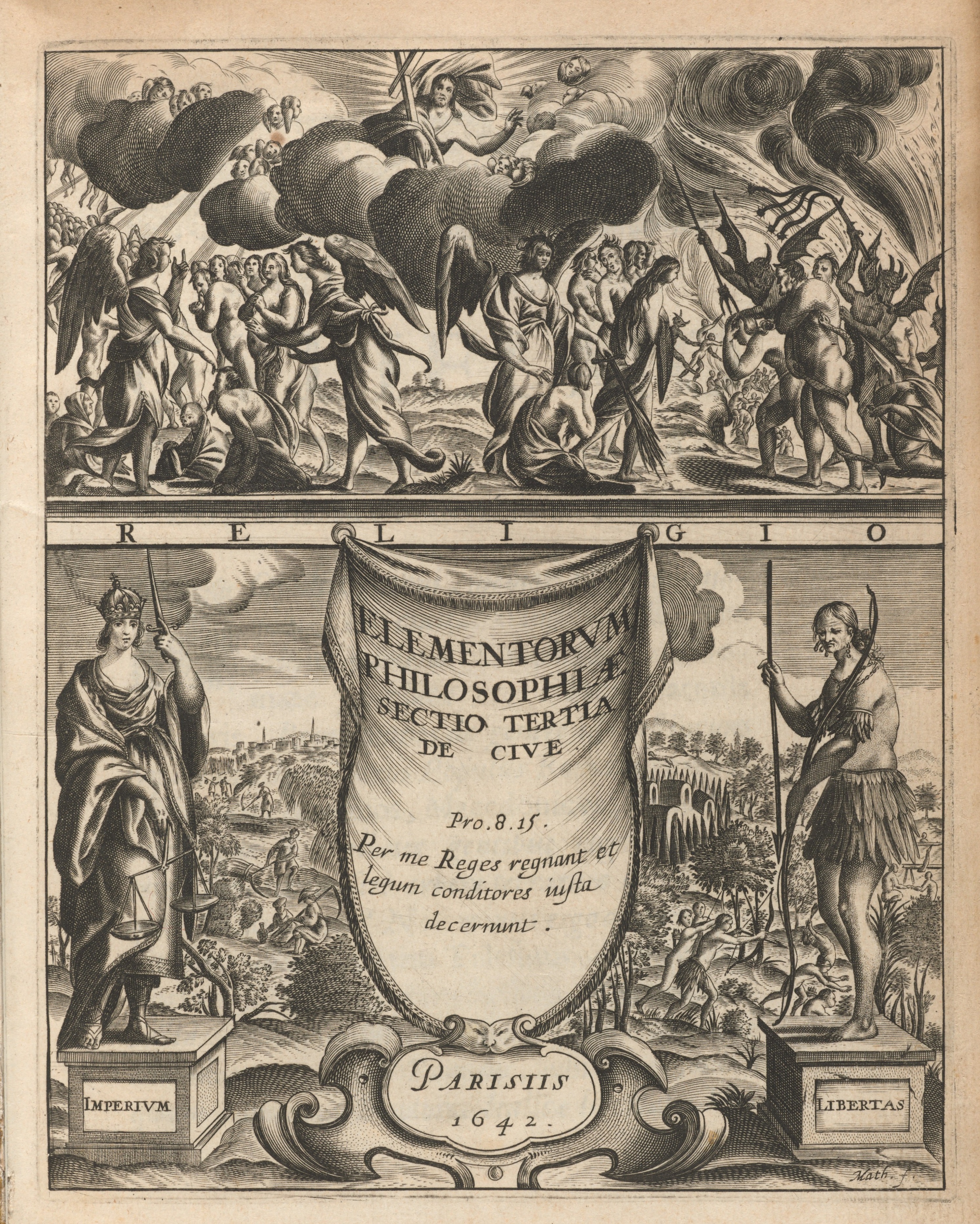

De Cive (Il Cittadino), pubblicato originariamente in latino, nel 1642 e, successivamente, in inglese, nel 1651, si colloca cronologicamente tra le due grandi opere di Thomas Hobbes, Leviatano (1651) e De Corpore (Il Corpo, 1655). Il contesto storico di De Cive è cruciale per comprenderne le tematiche. Hobbes scrive durante un periodo di instabilità in Inghilterra, caratterizzato dalla guerra civile (1642-1651). Il conflitto tra la monarchia di Carlo I e il Parlamento costituisce un retroscena di caos e incertezza, che influenza profondamente il pensiero di Hobbes. La sua speculazione filosofica è una risposta diretta al disordine e alla paura di anarchia che percepisce attorno a sé, cercando di trovare soluzioni teoriche per la pace e la stabilità sociale.

L’Autore sviluppa in quest’opera una visione del mondo radicalmente nuova e meccanicistica. L’uomo è visto come un corpo in movimento, guidato da appetiti e avversioni, le cui interazioni determinano la struttura della società. Nel trattare gli aspetti antropologici, Hobbes dipinge un ritratto dell’uomo mosso primariamente dall’istinto di autoconservazione. Questa concezione pessimistica dell’essere umano, essenzialmente egoista e trasportato dal desiderio di potere, è fondamentale per comprendere il suo appello a un’autorità assoluta.

Il filosofo introduce il concetto di stato di natura, in cui gli uomini sono liberi e uguali. Tale libertà, però, conduce inevitabilmente al conflitto. Da qui, l’esigenza di un potere sovrano che imponga l’ordine e garantisca la pace, attraverso il contratto sociale: gli individui cedono i loro diritti al sovrano in cambio di protezione, un’idea che avrebbe influenzato profondamente il pensiero politico successivo.

Hobbes approfondisce in modo significativo la distinzione tra lo stato di natura e lo stato civile, concetti fondamentali per la comprensione del suo pensiero politico e filosofico. Questi servono a fondare la sua rappresentazione del contratto sociale e a delineare la transizione necessaria dalla natura alla società, per garantire sicurezza e ordine civile.

Secondo Hobbes, lo stato di natura è una condizione ipotetica, in cui gli esseri umani vivono senza una struttura politico-legale superiore che regoli le loro interazioni. In De Cive, così come nel più celebre Leviatano, il filosofo descrive lo stato di natura con la famosa frase homo homini lupus (l’uomo è lupo per l’uomo). Non vi esistono leggi oltre ai desideri e alle paure individuali; è un ambiente in cui vigono il sospetto perpetuo e la paura della morte violenta. Tutti gli uomini sono uguali, nel senso che chiunque può uccidere chiunque altro, sia per proteggersi sia per prevenire potenziali danni. Di conseguenza, lo stato di natura è caratterizzato da una guerra di tutti contro tutti (bellum omnium contra omnes), la vita è “solitaria, povera, brutale, brutta e breve”, come scriverà poi in Leviatano.

La transizione dallo stato di natura allo stato civile avviene mediante il contratto sociale, un’idea che Hobbes sviluppa per spiegare come gli individui possano uscire dallo stato di natura. Sostiene, infatti, che questi, mossi dalla razionale paura della morte violenta e dal desiderio di una vita più sicura e produttiva, decidano di istituire un’autorità sovrana a cui cedere il proprio diritto naturale di governarsi autonomamente. Questo sovrano, o “Leviatano”, è autorizzato a detenere il potere assoluto per imporre l’ordine; non è parte del contratto sociale e, quindi, non è soggetto alle leggi che impone. La sua autorità deriva dalla consapevolezza collettiva che senza un tale potere la società regredirebbe allo stato di natura. Gli individui accettano di vivere sotto un’autorità assoluta per evitare il caos e la violenza che altrimenti prevarrebbero.

La contrapposizione tra stato di natura e stato civile ha profonde implicazioni filosofiche e politiche. Hobbes sfida le nozioni precedenti di società governata dalla morale o dal diritto naturale, sostituendo questo modello con la necessità di un potere sovrano e indiscutibile per mantenere l’ordine. La visione hobbesiana del contratto sociale ha influenzato profondamente la teoria politica moderna, anticipando questioni di consenso, diritti individuali e natura del potere politico. La sua analisi rimane pertinente per le discussioni contemporanee sui fondamenti della legittimità del governo e sui diritti degli individui rispetto al potere statale. La dicotomia tra stato di natura e stato civile, in definitiva, costituisce anche una riflessione profonda sulla condizione umana e sulla società.

In De Cive, Hobbes articola una visione del mondo e una filosofia politica che riflettono le sue profonde preoccupazioni riguardo alla natura umana e alla necessità di ordine. In un’epoca di grandi turbamenti propone una soluzione radicale al problema della coesistenza umana, ponendo le basi per la moderna teoria politica. L’opera, quindi, non solo riflette il tumulto del suo tempo, ma offre anche spunti di riflessione ancora attuali sulla natura del potere e sulla condizione umana.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, nel suo Discorso sull’origine e i fondamenti della diseguaglianza tra gli uomini, pubblicato nel 1755, esamina le radici profonde e le conseguenze della diseguaglianza umana, presentando una critica serrata alle società moderne, basate sulle istituzioni e sulla proprietà privata. Quest’opera si distingue quale uno dei testi fondamentali nella storia della filosofia politica e sociale, proponendo una riflessione profonda che interpella ancora oggi il lettore su temi di bruciante attualità.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, nel suo Discorso sull’origine e i fondamenti della diseguaglianza tra gli uomini, pubblicato nel 1755, esamina le radici profonde e le conseguenze della diseguaglianza umana, presentando una critica serrata alle società moderne, basate sulle istituzioni e sulla proprietà privata. Quest’opera si distingue quale uno dei testi fondamentali nella storia della filosofia politica e sociale, proponendo una riflessione profonda che interpella ancora oggi il lettore su temi di bruciante attualità.

Utopia, pubblicata nel 1516 da Thomas More, è un’opera che non solo ha introdotto un nuovo genere letterario, quello della letteratura utopica, ma ha anche offerto uno spaccato profondo delle tensioni politiche e filosofiche del Cinquecento inglese ed europeo. Attraverso la descrizione di un’isola immaginaria e della sua società ideale, More esplora temi di giustizia sociale, organizzazione politica e morale individuale.

Utopia, pubblicata nel 1516 da Thomas More, è un’opera che non solo ha introdotto un nuovo genere letterario, quello della letteratura utopica, ma ha anche offerto uno spaccato profondo delle tensioni politiche e filosofiche del Cinquecento inglese ed europeo. Attraverso la descrizione di un’isola immaginaria e della sua società ideale, More esplora temi di giustizia sociale, organizzazione politica e morale individuale.