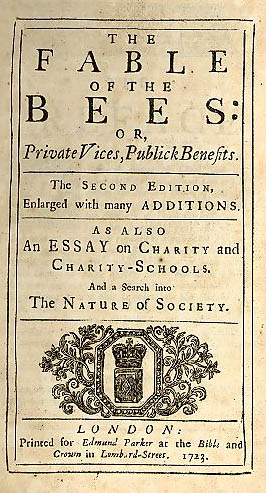

Bernard de Mandeville (1670-1733), medico e filosofo di origini olandesi, naturalizzato inglese, pubblicò la sua opera più celebre, La favola delle api: vizi privati, pubbliche virtù (The Fable of the Bees: or, Private Vices, Publick Benefits), nel 1714. Questo poemetto satirico è un testo provocatorio e fondamentale per comprendere le radici del pensiero economico moderno e le tensioni etiche della società capitalistica emergente.

Bernard de Mandeville (1670-1733), medico e filosofo di origini olandesi, naturalizzato inglese, pubblicò la sua opera più celebre, La favola delle api: vizi privati, pubbliche virtù (The Fable of the Bees: or, Private Vices, Publick Benefits), nel 1714. Questo poemetto satirico è un testo provocatorio e fondamentale per comprendere le radici del pensiero economico moderno e le tensioni etiche della società capitalistica emergente.

Mandeville si stabilì in Inghilterra durante un periodo di profonde trasformazioni sociali ed economiche. Tra il XVII e il XVIII secolo, l’Europa attraversava una fase di grandi cambiamenti, segnati dall’ascesa della borghesia, dallo sviluppo del capitalismo e dalla nascita delle prime teorie economiche moderne. L’Illuminismo, pur celebrando la razionalità e i princìpi morali, fu anche un’epoca di critica alle istituzioni religiose e alle concezioni tradizionali della virtù. In questo contesto, Mandeville si distinse come una voce provocatoria e cinica, capace di mettere in discussione le fondamenta stesse del pensiero etico e sociale. L’Inghilterra del tempo stava conoscendo una rapida espansione economica, trainata dallo sviluppo del commercio globale, dai progressi tecnologici e dall’incremento del sistema bancario. Questo scenario portò a riflessioni inedite sul ruolo delle motivazioni umane nella prosperità collettiva. Mandeville, con La favola delle api, sovvertì l’idea tradizionale che il benessere della società derivasse dalla virtù, sostenendo invece che il vizio e l’interesse personale fossero il vero motore del progresso economico e sociale.

La favola delle api è strutturata in una combinazione di poesia e saggi filosofici. L’opera si apre con la poesia allegorica The Grumbling Hive: or, Knaves Turn’d Honest (L’alveare brontolone, o i furfanti resi onesti), che racconta in forma simbolica la storia di un alveare prospero, in cui ogni ape agisce in modo egoistico e spesso moralmente riprovevole. Tuttavia, questi vizi individuali si rivelano indispensabili per il benessere collettivo dell’alveare. Quando le api decidono di riformarsi e adottare una condotta morale virtuosa, l’alveare collassa, portando miseria e declino. Accanto alla poesia, Mandeville aggiunse, nelle edizioni successive, una serie di saggi esplicativi e note in cui approfondisce i temi principali, sviluppando riflessioni più articolate sul rapporto tra etica, economia e società. In alcune sezioni dialogiche, l’autore risponde alle critiche ricevute, spiegando la sua visione in modo più dettagliato e cercando di chiarire i malintesi che il suo lavoro aveva generato.

La poesia centrale dell’opera utilizza l’alveare come una metafora della società umana. In questo alveare, ogni ape persegue i propri interessi personali, agendo in modo egoistico e spesso moralmente discutibile, ma il risultato è una prosperità collettiva. L’avidità stimola il commercio, il lusso sostiene l’industria e l’arte e persino i comportamenti illegali creano occupazione, alimentando il sistema economico. Tuttavia, quando le api scelgono di abbandonare i propri vizi e di vivere secondo principi di virtù e onestà, l’alveare crolla. Rinunciando alle attività economiche che erano motivate dai vizi, l’alveare si impoverisce e torna a uno stato primitivo.

Questo paradosso centrale illustra l’idea controversa di Mandeville: ciò che è moralmente condannabile a livello individuale può essere benefico per la società nel suo complesso. La prosperità, secondo questa visione, non deriva dalla virtù, ma dalla gestione funzionale delle passioni e degli interessi egoistici.

Uno dei temi fondamentali dell’opera è il paradosso morale che lega i vizi privati alle pubbliche virtù. Mandeville sostiene che il benessere collettivo si fondi sulla ricerca egoistica del proprio interesse e che i comportamenti moralmente riprovevoli, come l’avidità e l’ambizione, siano in realtà indispensabili per il progresso economico. Questa visione anticipa, in parte, il pensiero di Adam Smith, anche se Mandeville adotta un tono più cinico, evidenziando come i vizi siano parte integrante della natura umana.

Un altro tema cruciale è la critica all’ipocrisia sociale. L’autore denuncia come le istituzioni religiose e politiche condannino ufficialmente il vizio, pur beneficiando implicitamente delle sue conseguenze economiche. L’ipocrisia delle élite viene messa in evidenza come uno dei pilastri su cui si regge la società capitalistica nascente.

Mandeville riflette anche sulla natura umana, descrivendola come intrinsecamente egoistica e passionale. Contrariamente a molti filosofi illuministi, che vedevano nella ragione il fondamento dell’ordine morale, egli sottolinea l’importanza delle passioni e degli istinti. Cercare di eliminare i vizi, secondo Mandeville, significa opporsi alla natura stessa e privare la società del suo principale motore di progresso.

Un altro aspetto importante è l’interdipendenza economica. Mandeville descrive la società come un sistema complesso, in cui ogni attività, anche la più immorale, contribuisce al benessere collettivo. Questa visione anticipa alcune delle teorie economiche moderne, sottolineando l’importanza del consumo e della spesa per sostenere l’economia.

Infine, l’autore mette in discussione l’idea di una società utopica basata esclusivamente sulla virtù. La storia dell’alveare dimostra che un sistema fondato su un’etica rigorosa e sulla purezza morale non è sostenibile. Al contrario, il progresso umano richiede compromessi e l’accettazione delle imperfezioni.

L’opera di Mandeville fu accolta con polemiche e critiche feroci. Molti contemporanei lo accusarono di giustificare il vizio e di promuovere una visione amorale della società. Filosofi come Joseph Butler e George Berkeley criticarono apertamente le sue teorie, considerandole pericolose e distruttive per i valori morali. Tuttavia, nonostante le polemiche, La favola delle api esercitò una profonda influenza sul pensiero economico e filosofico.

In ambito economico, Mandeville gettò le basi per il liberalismo economico, anticipando l’idea che l’interesse personale, se opportunamente incanalato, possa generare benefici collettivi. In filosofia morale, le sue riflessioni stimolarono il dibattito sul rapporto tra etica e politica, mentre in sociologia la sua opera rappresentò uno dei primi tentativi di analizzare le dinamiche sociali in modo realistico, mettendo in evidenza il ruolo delle istituzioni nel gestire i comportamenti individuali.

La favola delle api è un’opera che, nonostante la sua apparente semplicità allegorica, contiene riflessioni profonde e provocatorie sul rapporto tra morale, economia e progresso sociale. Mandeville invita il lettore a confrontarsi con le contraddizioni intrinseche della società moderna, in cui ciò che appare moralmente discutibile può rivelarsi indispensabile per il benessere collettivo. La sua visione, cinica ma realistica, continua a suscitare interrogativi sulla natura umana e sulle dinamiche che governano la prosperità delle società. Sebbene controversa, quest’opera rimane un punto di riferimento fondamentale per chiunque voglia comprendere le origini e le complessità del pensiero economico moderno.

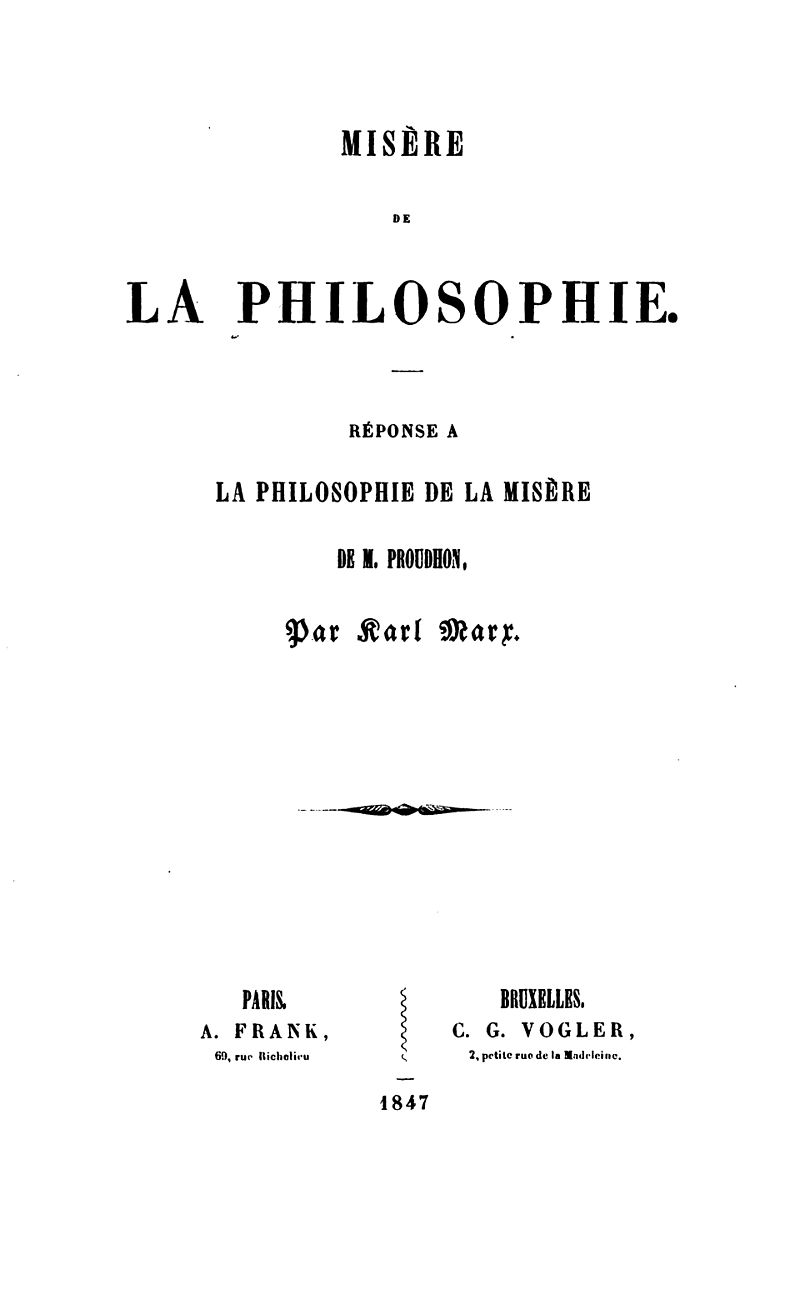

La miseria della filosofia di Karl Marx, pubblicata nel 1847, è una delle opere più significative del pensiero marxiano, imperniata su una critica serrata alle teorie di Pierre-Joseph Proudhon e alla sua Philosophie de la misère (1846). Nella prima metà del XIX secolo, l’espansione del capitalismo stava generando una rapida crescita economica, accompagnata da disuguaglianze sempre più marcate tra le classi sociali. La borghesia industriale si affermava come classe dominante, mentre la classe operaia, vittima di sfruttamento e di dure condizioni di lavoro, cominciava a organizzarsi per rivendicare diritti e condizioni più eque. In questo contesto, il socialismo emergeva come un movimento articolato in diverse correnti e interpretazioni. Proudhon, tra i principali teorici del socialismo francese, tentava di proporre soluzioni ai problemi della società capitalista, combinando filosofia, economia e morale. Tuttavia, la sua opera, pur animata da uno spirito progressista, fu considerata da Marx teoricamente incoerente e insufficiente per affrontare le contraddizioni del capitalismo. Esiliato a Bruxelles, Marx stava sviluppando il suo materialismo storico, approfondendo l’analisi sull’economia politica e sulla storia. La critica a Proudhon costituì per lui l’occasione di affinare il proprio pensiero, differenziando il socialismo scientifico da quello utopistico.

La miseria della filosofia di Karl Marx, pubblicata nel 1847, è una delle opere più significative del pensiero marxiano, imperniata su una critica serrata alle teorie di Pierre-Joseph Proudhon e alla sua Philosophie de la misère (1846). Nella prima metà del XIX secolo, l’espansione del capitalismo stava generando una rapida crescita economica, accompagnata da disuguaglianze sempre più marcate tra le classi sociali. La borghesia industriale si affermava come classe dominante, mentre la classe operaia, vittima di sfruttamento e di dure condizioni di lavoro, cominciava a organizzarsi per rivendicare diritti e condizioni più eque. In questo contesto, il socialismo emergeva come un movimento articolato in diverse correnti e interpretazioni. Proudhon, tra i principali teorici del socialismo francese, tentava di proporre soluzioni ai problemi della società capitalista, combinando filosofia, economia e morale. Tuttavia, la sua opera, pur animata da uno spirito progressista, fu considerata da Marx teoricamente incoerente e insufficiente per affrontare le contraddizioni del capitalismo. Esiliato a Bruxelles, Marx stava sviluppando il suo materialismo storico, approfondendo l’analisi sull’economia politica e sulla storia. La critica a Proudhon costituì per lui l’occasione di affinare il proprio pensiero, differenziando il socialismo scientifico da quello utopistico. Marx accusò Proudhon di un approccio superficiale e idealistico, basato su una presunta scienza universale dell’economia fondata su princìpi di giustizia eterna. Per esempio, Proudhon proponeva una “banca del popolo” per offrire credito senza interessi e un sistema di scambio fondato sul valore del lavoro. Marx stroncava tutto ciò, sostenendo che il problema centrale risiedesse nella struttura stessa del capitalismo, basata sulla proprietà privata dei mezzi di produzione e sullo sfruttamento del lavoro salariato.

Marx accusò Proudhon di un approccio superficiale e idealistico, basato su una presunta scienza universale dell’economia fondata su princìpi di giustizia eterna. Per esempio, Proudhon proponeva una “banca del popolo” per offrire credito senza interessi e un sistema di scambio fondato sul valore del lavoro. Marx stroncava tutto ciò, sostenendo che il problema centrale risiedesse nella struttura stessa del capitalismo, basata sulla proprietà privata dei mezzi di produzione e sullo sfruttamento del lavoro salariato.

Nel magnum opus Due trattati sul governo, pubblicata anonima nel 1690, John Locke tesse una tela intricata e raffinata di idee, che hanno plasmato i fondamenti del pensiero liberale moderno. Quest’opera non è un semplice trattato politico, ma attraversa l’essenza stessa della libertà e della legittimità politica, un inno ai diritti innati dell’individuo e alla sovranità del popolo.

Nel magnum opus Due trattati sul governo, pubblicata anonima nel 1690, John Locke tesse una tela intricata e raffinata di idee, che hanno plasmato i fondamenti del pensiero liberale moderno. Quest’opera non è un semplice trattato politico, ma attraversa l’essenza stessa della libertà e della legittimità politica, un inno ai diritti innati dell’individuo e alla sovranità del popolo.

L’etica protestante e lo spirito del capitalismo di Max Weber, pubblicata nel 1905, è un’opera fondamentale che sonda l’influenza della religione sullo sviluppo economico e culturale dell’Occidente. Attraverso un’analisi meticolosa e interdisciplinare, l’Autore intreccia filosofia, storia, letteratura e religione, per rivelare come l’etica protestante abbia contribuito a modellare il moderno capitalismo.

L’etica protestante e lo spirito del capitalismo di Max Weber, pubblicata nel 1905, è un’opera fondamentale che sonda l’influenza della religione sullo sviluppo economico e culturale dell’Occidente. Attraverso un’analisi meticolosa e interdisciplinare, l’Autore intreccia filosofia, storia, letteratura e religione, per rivelare come l’etica protestante abbia contribuito a modellare il moderno capitalismo.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, nel suo Discorso sull’origine e i fondamenti della diseguaglianza tra gli uomini, pubblicato nel 1755, esamina le radici profonde e le conseguenze della diseguaglianza umana, presentando una critica serrata alle società moderne, basate sulle istituzioni e sulla proprietà privata. Quest’opera si distingue quale uno dei testi fondamentali nella storia della filosofia politica e sociale, proponendo una riflessione profonda che interpella ancora oggi il lettore su temi di bruciante attualità.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, nel suo Discorso sull’origine e i fondamenti della diseguaglianza tra gli uomini, pubblicato nel 1755, esamina le radici profonde e le conseguenze della diseguaglianza umana, presentando una critica serrata alle società moderne, basate sulle istituzioni e sulla proprietà privata. Quest’opera si distingue quale uno dei testi fondamentali nella storia della filosofia politica e sociale, proponendo una riflessione profonda che interpella ancora oggi il lettore su temi di bruciante attualità.