Taken from my lectures as a Teaching Fellow in International Law, these reflections highlight how State sovereignty and International Law are profoundly influenced by globalization, economic integration and digital technologies, raising fundamental questions about global governance, State autonomy and the adaptation of legal structures to new economic and technological realities.

Part III

Globalization and political power

The economic globalization has fundamentally redefined the relationship with State-imposed regulations, turning it fluid, unstable, and continuously evolving. The contraction of space and time, driven by technological progress, culminates in the obliteration of physical distances; an emblematic phenomenon of our digital age. Technology, by erasing geographical boundaries, ushers in a new global order, a boundaryless mosaic where time seems to condense into an ethereal instant and physical reality transforms into a digital domain, dissolving matter into a virtual ether. The current era witnesses the merging of the real and the virtual into a singular, indistinguishable reality that is simultaneously dual-faced, surpassing the traditional dichotomy. This fusion marks the end of the national borders era, propelling us into a homogenized global dimension, where unified space heralds an era of universal time.

In the realm of transnational dynamics, an identity emerges that is hybrid, devoid of territorial roots, challenging conventional social and political categories, transforming the legal framework in response to the demands of a global market. In this context, transnational corporations sketch a new order – a “nomos” – that navigates between the local and the global, between the aspirations of a borderless market and the constraints of nation-States, reflecting the complexity of an interconnected world.

The re-evaluation of the State in the global age reveals a radical transformation: the State, traditionally a pillar of authority, power, and decision-making, confronts the pervasiveness of the global economy and the thinning of its sovereignty. Digital technologies and the Internet rewrite the geopolitical rules, eroding the territorial foundations of State sovereignty and promoting an economy’s de-territorialization that transcends national borders, ushering in an era of interconnected global markets elusive to definite localization.

Against this backdrop, new geometries of power and law emerge, where the virtual reality of the economy and the tangible reality of law intertwine, outlining a landscape where transnational dynamics redefine the relationship between State and market. Economic globalization challenges State supremacy, giving rise to an era of reversals: the market assumes a position of dominance over the State, redefining traditional hierarchies and marking a profound discontinuity between the national dimensions of law and the transnational dimensions of the economy.

In this fluid and dynamic context, transnational corporations emerge as new protagonists, shaping legal and economic spaces according to logics independent of State sovereignty. The transnational economic reality and national law coexist in constant tension, reflecting the complexity of a world where old certainties are questioned, and new forms of dominance and resistance emerge. In such a landscape, a new binary order of dominators and dominated manifests, a dichotomy reflecting the inherent inequalities of the globalization era, where technology and finance rewrite the rules of the game, relegating many to the margins of a system that privileges a few chosen ones.

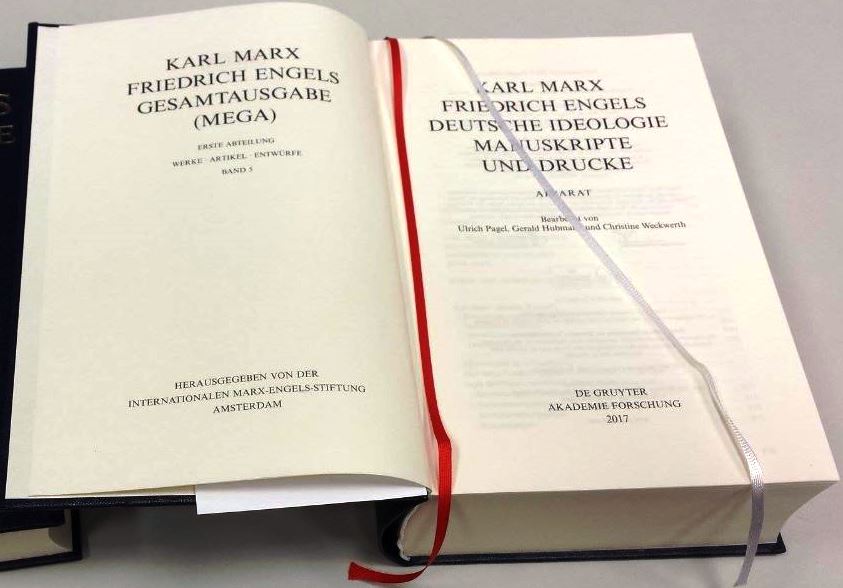

L’ideologia tedesca di Karl Marx, scritta con Friedrich Engels tra il novembre del 1846 e l’agosto del 1846, è un’opera fondamentale nel corpus teorico marxista, essenziale per comprendere l’evoluzione del pensiero del filosofo di Treviri, che lo conduce a una visione più strutturata del materialismo storico. Rimasta pressoché inedita durante la vita degli autori, fu pubblicata postuma solo nel 1932.

L’ideologia tedesca di Karl Marx, scritta con Friedrich Engels tra il novembre del 1846 e l’agosto del 1846, è un’opera fondamentale nel corpus teorico marxista, essenziale per comprendere l’evoluzione del pensiero del filosofo di Treviri, che lo conduce a una visione più strutturata del materialismo storico. Rimasta pressoché inedita durante la vita degli autori, fu pubblicata postuma solo nel 1932.