Le prove dell’esistenza di Dio sono un argomento che da sempre mi affascina, tanto da costituire una delle tematiche che spesso occupano le mie riflessioni e i miei scritti. La rilettura del De libero arbitrio di Agostino mi ha fornito uno spunto nuovo e sorprendente. Nel secondo libro di questa celebre opera, il dialogo tra Agostino ed Evodio introduce una dimostrazione che unisce una raffinata speculazione filosofica a una profonda intuizione teologica, trovando il suo fondamento ultimo nel concetto di verità.

Agostino, nella sua ricerca di Dio, parte non da una deduzione astratta o da un’idea ipotetica, ma dalla realtà stessa. Egli identifica tre aspetti fondamentali dell’esperienza umana, che sono indubitabili e autoevidenti: l’essere, il vivere e l’intendere. Questi tre elementi non possono essere messi in discussione, poiché si impongono alla nostra coscienza con una forza tale da rendere ogni negazione un’implicita affermazione della loro verità. L’essere: il fatto stesso di esistere è una verità che nessuno può negare, poiché il negare presuppone un’esistenza che lo renda possibile. Non posso dubitare di esistere senza affermare, nel dubbio stesso, la mia esistenza. Il vivere: non solo esistiamo, ma viviamo, cioè partecipiamo a un’esperienza che va oltre il semplice essere. Vivere implica sensibilità, movimento, attività, e anche questa dimensione è autoevidente. L’intendere: infine, intendiamo, cioè siamo in grado di comprendere, percepire la realtà e riflettere su di essa. Anche questa capacità non può essere negata senza contraddirsi, poiché negare implica un atto di comprensione. Questi tre aspetti sono quindi veri in modo immediato e indiscutibile. Essi non derivano da un ragionamento complesso, ma si presentano come dati primari della nostra esperienza.

Agostino, tuttavia, non si accontenta di constatare la realtà di essere, vivere e intendere. Egli si chiede: cosa accomuna questi tre elementi? La risposta risiede nella loro verità. Se esistono, se sono evidenti, allora sono veri. Ma questa verità non può essere ridotta alle cose stesse o all’intelletto umano che le riconosce. La verità è qualcosa di più: è un fondamento che trascende il contingente e il mutevole.

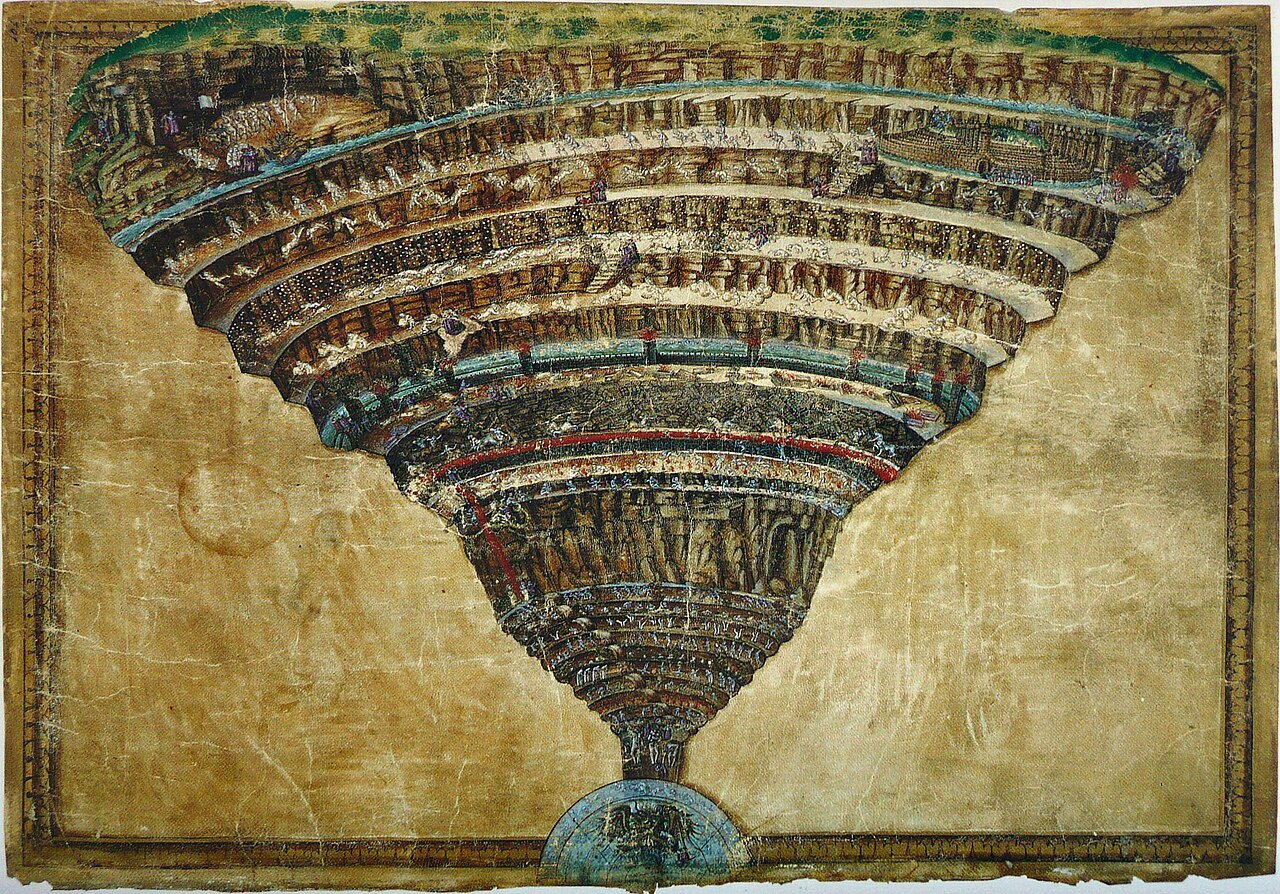

Qui il pensiero di Agostino compie un salto decisivo. Egli mostra che la verità, per essere tale, non può dipendere dal nostro pensiero né da alcun aspetto particolare della realtà. Deve essere assoluta, cioè indipendente da tutto ciò che è relativo; deve essere eterna, poiché una verità che cambia cesserebbe di essere tale; deve essere trascendente, ossia esistere al di là del mondo materiale e delle limitazioni umane. Questa verità, dunque, è realtà suprema e universale. Ed è proprio questa trascendenza che porta Agostino a identificarla con Dio.

Arriviamo così al cuore dell’argomentazione: se la verità è assoluta, eterna e trascendente, allora coincide necessariamente con ciò che intendiamo per Dio. Dio, infatti, è da sempre concepito come la realtà suprema, immutabile, fonte di ogni esistenza e conoscenza. In altre parole, la verità, intesa come principio fondamentale e autosufficiente, non può che essere Dio stesso. Questa dimostrazione si distingue per la sua raffinatezza e per la capacità di radicare il concetto di Dio in un’esperienza universale e condivisibile. Non si tratta di un’argomentazione che presuppone una fede già data, ma di un ragionamento che parte da ciò che chiunque può riconoscere come vero.

Interessante è il legame con il neoplatonismo, da cui Agostino trae ispirazione. La sua idea di una verità trascendente che dà senso al mondo ricorda la dottrina dell’Uno e del Nous di Plotino, ma il pensiero cristiano introduce una dimensione personale e relazionale, identificando questa verità con un Dio vivo e creatore. La dimostrazione di Agostino, poi, anticipa, per certi aspetti, altre celebri prove dell’esistenza di Dio, in particolare quella ontologica di Anselmo d’Aosta. Anche Anselmo, infatti, individua in Dio il fondamento ultimo della realtà, definendolo come “ciò di cui non si può pensare il maggiore”. Tuttavia, mentre Anselmo si muove in un ambito strettamente logico, Agostino parte dall’esperienza concreta e dalla percezione immediata della verità.