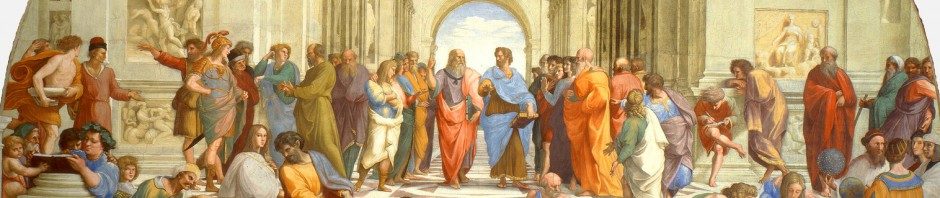

De divisione naturae, conosciuto anche con il titolo greco Periphyseon, è l’opera maggiore di Giovanni Scoto Eriugena, pensatore irlandese del IX secolo, attivo alla corte carolingia di Carlo il Calvo. Quest’opera monumentale costituisce uno dei tentativi più originali e audaci del Medioevo di costruire un sistema filosofico e teologico capace di integrare la rivelazione cristiana con le strutture speculative del neoplatonismo tardo-antico. Scritta in un latino raffinato e spesso complesso, è organizzata in forma dialogica, con l’alternanza tra maestro e discepolo, un espediente che permette all’autore di esaminare e discutere i concetti da più angolazioni, senza appiattirli in un’esposizione lineare.

L’opera si fonda su una visione della realtà strutturata in quattro modalità fondamentali dell’essere, che Eriugena definisce “nature”. Non si tratta di categorie fisse, né di enti distinti, ma di modalità dinamiche in cui si articola il rapporto tra Dio, la creazione e il ritorno finale di tutte le cose all’origine divina. La prima natura è Dio in quanto principio assoluto, che crea tutto ma non è creato da nulla. È la fonte inesauribile dell’essere, trascendente e inconoscibile, che si colloca al di là di ogni determinazione. La seconda natura comprende le cause primarie e le idee eterne che risiedono nella mente divina e che partecipano all’atto creativo: sono forme intelligibili che danno struttura alla realtà creata. La terza natura è l’universo sensibile, la realtà materiale e visibile, che riceve la forma ma non è in grado di produrne a sua volta. La quarta e ultima natura è Dio come fine supremo, il termine verso cui tutto tende. In questa visione, Dio è sia origine che destinazione: tutto ha inizio in Lui e tutto ritorna a Lui, in un movimento circolare che richiama esplicitamente la metafisica neoplatonica del processus e reditus.

Questa visione non è puramente teorica ma si innesta in una riflessione più ampia sulla conoscenza, sul linguaggio e sulla funzione della filosofia e della teologia. Per Eriugena, non esiste separazione tra ragione e fede: la filosofia autentica è essa stessa teologia e la teologia non può che essere esercizio della ragione. Questo principio lo porta ad affermare che nulla di ciò che è in contrasto con la ragione può provenire da una vera autorità, anche se ecclesiastica. Una tesi che, per i suoi tempi, era estremamente ardita. La ragione, dunque, non è nemica della fede ma suo completamento e strumento privilegiato per cogliere il senso profondo della rivelazione.

Un tema centrale dell’opera è il concetto di logos, inteso come parola divina ma anche come ragione universale che permea la creazione. Il mondo, per Eriugena, è una sorta di “testo” scritto da Dio, e l’uomo, attraverso la sua intelligenza, è chiamato a leggerlo e interpretarlo. La conoscenza non è mai separata dalla contemplazione del divino ed è proprio tramite questa attività interpretativa che l’essere umano realizza la sua natura più autentica.

In questo sistema, l’uomo occupa una posizione privilegiata. Non è soltanto parte del creato ma è altresì immagine di Dio, contenendo in sé tutti gli elementi della realtà. Per questa ragione, Eriugena lo definisce microcosmo, cioè un riassunto dell’universo. L’essere umano, in quanto creatura razionale e spirituale, è l’anello di congiunzione tra il mondo sensibile e quello intelligibile. In lui si realizza la sintesi di tutte le nature. È attraverso l’uomo che la creazione prende coscienza di sé e può, mediante un processo di purificazione e conoscenza, ritornare al proprio principio.

Una riflessione importante riguarda anche il problema del male. Eriugena lo interpreta in continuità con la tradizione agostiniana e neoplatonica, sostenendo che il male non ha consistenza ontologica: non è una realtà creata, quanto una privazione, un’assenza del bene. Il male è, quindi, non-essere, disordine, deviazione rispetto alla pienezza dell’essere che è Dio. Perciò, non si può attribuire a Dio la responsabilità del male, perché Dio è solo bene, e tutto ciò che esiste veramente partecipa del bene.

Nonostante l’elevata coerenza speculativa del sistema, il pensiero di Eriugena fu accolto con diffidenza. Le sue tesi, specie quelle che sembravano dissolvere la distinzione tra creatore e creato nel ritorno finale a Dio, furono ritenute ambigue e pericolose. Nel XIII secolo, l’opera fu condannata come eretica dal concilio di Sens (1225) e da papa Onorio III, e ne fu proibita la lettura. Per secoli, il De divisione naturae è rimasto ai margini della tradizione scolastica, ma è stato riscoperto in epoca moderna come un’opera di straordinaria originalità.

Oggi, De divisione naturae è considerato un testo filosofico e teologico di primo piano nell’Alto Medioevo, capace di anticipare temi che sarebbero diventati centrali nella scolastica, nel misticismo renano e nella metafisica dell’età moderna. La sua riflessione sulla natura, sull’unità dell’essere, sulla funzione della ragione e sul destino dell’uomo si colloca in un punto di snodo tra la cultura tardo-antica e la filosofia cristiana medievale, rendendo Giovanni Scoto Eriugena una figura chiave nella storia del pensiero occidentale.

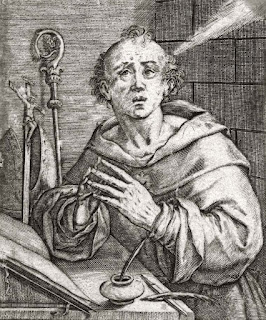

Accanto a Eckhart si colloca Johannes Tauler, anch’egli domenicano, ma di temperamento più pratico e pastorale. Vissuto tra il 1300 e il 1361, Tauler è noto per le sue prediche, rivolte non solo ai monaci ma anche a laici spiritualmente impegnati, in particolare donne appartenenti ai circoli delle beghine. Il suo stile è meno astratto di quello di Eckhart e più attento alla concretezza della vita spirituale. Tauler parla dell’importanza dell’umiltà, della pazienza nella sofferenza, del lavoro interiore come via per accogliere la grazia divina. Anche per lui Dio abita nel profondo dell’anima, ma il cammino per raggiungerlo passa attraverso prove, silenzi e oscurità interiori. Il mistico, nella visione di Tauler, non è qualcuno che fugge dal mondo, ma colui che impara a vivere in esso con uno sguardo purificato, capace di vedere il divino anche nella fatica quotidiana.

Accanto a Eckhart si colloca Johannes Tauler, anch’egli domenicano, ma di temperamento più pratico e pastorale. Vissuto tra il 1300 e il 1361, Tauler è noto per le sue prediche, rivolte non solo ai monaci ma anche a laici spiritualmente impegnati, in particolare donne appartenenti ai circoli delle beghine. Il suo stile è meno astratto di quello di Eckhart e più attento alla concretezza della vita spirituale. Tauler parla dell’importanza dell’umiltà, della pazienza nella sofferenza, del lavoro interiore come via per accogliere la grazia divina. Anche per lui Dio abita nel profondo dell’anima, ma il cammino per raggiungerlo passa attraverso prove, silenzi e oscurità interiori. Il mistico, nella visione di Tauler, non è qualcuno che fugge dal mondo, ma colui che impara a vivere in esso con uno sguardo purificato, capace di vedere il divino anche nella fatica quotidiana.

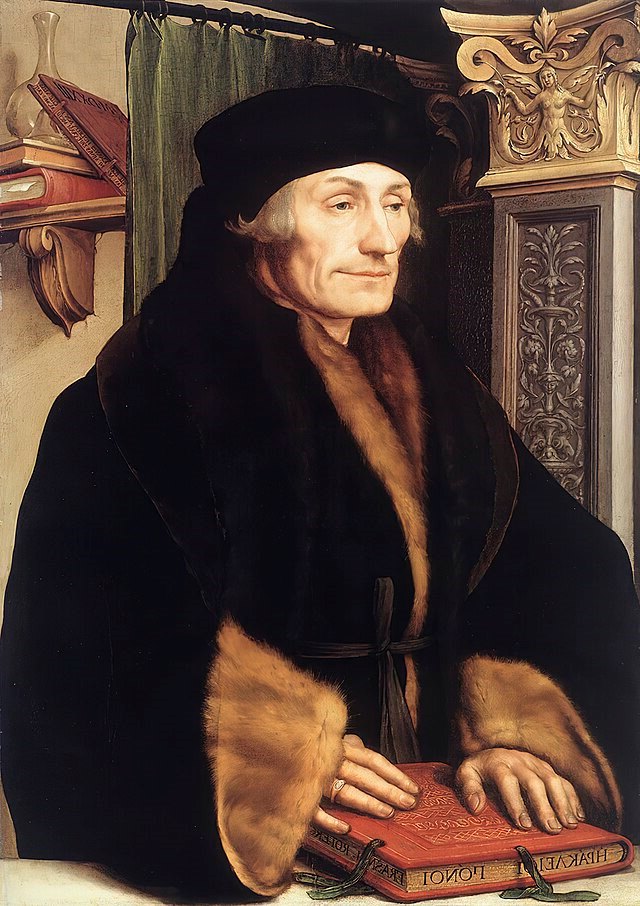

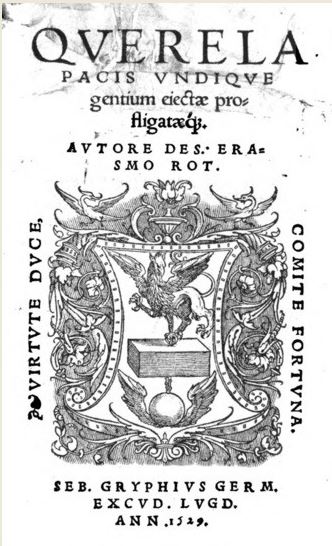

Querela Pacis, o Il Lamento della Pace, è un’opera di Erasmo da Rotterdam, composta nel 1517. Il celebre umanista olandese, una delle figure più autorevoli del Rinascimento europeo, concepì questo testo come un appello accorato alla pace, contrapponendosi alla violenza e alle guerre che dilaniavano il continente, criticando lucidamente e appassionatamente l’assurdità della guerra.

Querela Pacis, o Il Lamento della Pace, è un’opera di Erasmo da Rotterdam, composta nel 1517. Il celebre umanista olandese, una delle figure più autorevoli del Rinascimento europeo, concepì questo testo come un appello accorato alla pace, contrapponendosi alla violenza e alle guerre che dilaniavano il continente, criticando lucidamente e appassionatamente l’assurdità della guerra.