Utopia, pubblicata nel 1516 da Thomas More, è un’opera che non solo ha introdotto un nuovo genere letterario, quello della letteratura utopica, ma ha anche offerto uno spaccato profondo delle tensioni politiche e filosofiche del Cinquecento inglese ed europeo. Attraverso la descrizione di un’isola immaginaria e della sua società ideale, More esplora temi di giustizia sociale, organizzazione politica e morale individuale.

Utopia, pubblicata nel 1516 da Thomas More, è un’opera che non solo ha introdotto un nuovo genere letterario, quello della letteratura utopica, ma ha anche offerto uno spaccato profondo delle tensioni politiche e filosofiche del Cinquecento inglese ed europeo. Attraverso la descrizione di un’isola immaginaria e della sua società ideale, More esplora temi di giustizia sociale, organizzazione politica e morale individuale.

L’Autore scrive Utopia nel contesto dell’Inghilterra del XVI secolo, un periodo di grandi cambiamenti e di instabilità politica. L’Europa è attraversata dalle prime ondate di Riforma protestante e dalla dissoluzione dei monopoli ecclesiastici, mentre i regni si trovano a navigare le complesse dinamiche del capitalismo nascente. In questo quadro, More, uomo di legge e Lord Cancelliere sotto Enrico VIII, propone un modello di convivenza che critica tanto le monarchie assolute quanto le tensioni economiche prodotte dall’emergente mercantilismo.

Il libro è diviso in due parti: la prima contiene una critica pungente delle politiche europee dell’epoca, specialmente quelle inglesi, mentre la seconda descrive l’isola di Utopia. Questa divisione riflette la doppia visione di More che, da un lato, denuncia le ingiustizie del suo tempo e, dall’altro, propone un modello alternativo basato su principi di equità e comunanza delle risorse.

Utopia è rappresentata come una società che ha abolito la proprietà privata, dove i beni sono condivisi e l’avidità è vista come un vizio non solo morale ma anche sociale. Il lavoro è obbligatorio per tutti, garantendo che nessuno possa accumulare ricchezze a discapito di altri. More introduce anche un sistema educativo avanzato e inclusivo, mirato al miglioramento morale oltre che intellettuale.

L’opera è ricca di implicazioni filosofiche che non solo delineano una critica sociale, ma invitano anche a un esame delle basi etiche e dei principi su cui si potrebbe costruire una società ideale.

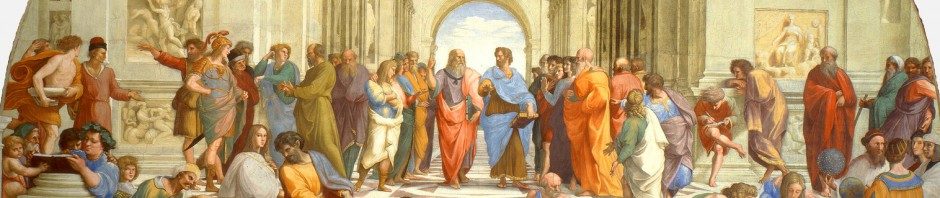

La nozione di bene comune è centrale in Utopia. More immagina una società dove la proprietà privata non esista; tutti i beni sono di proprietà comune e gestiti dallo Stato. Ciò elimina non solo la povertà, ma anche l’invidia e il crimine che, secondo l’Autore, sono spesso prodotti dalla disuguaglianza economica. Questa visione utopica riflette influenze platoniche, in particolare l’idea della proprietà comune tra i guardiani nel dialogo Repubblica. More utilizza questo modello per criticare le ingiustizie del capitalismo nascente, proponendo un’alternativa radicale che oggi potremmo associare al comunismo utopico.

Il lavoro, poi, è obbligatorio per tutti i cittadini e si basa su un’etica che valorizza il contributo individuale al bene comune. Questo non solo assicura che ogni individuo contribuisca alla società, ma promuove anche un senso di solidarietà e cooperazione. L’obbligo di lavorare riduce la dipendenza da servitù o schiavitù, concetti molto presenti nell’Europa del XVI secolo. La visione di More sul lavoro come dovere sociale e fonte di realizzazione individuale anticipa discussioni moderne sull’etica del lavoro e sul suo ruolo nell’autorealizzazione.

L’approccio di More alla legalità è notevolmente progressista. Le leggi sono poche e semplici, progettate per essere facilmente comprensibili da tutti i cittadini, evitando così la corruzione e l’abuso di potere, che spesso accompagnano sistemi legali complessi e arcuati. Inoltre, il sistema giuridico di Utopia è orientato più alla prevenzione del crimine e alla rieducazione del criminale che non al suo semplice castigo. Questa visione riformista della legge come strumento di giustizia sociale riflette le idee dell’Autore sulla moralità applicata alla legislazione, dove le pene severe sono rare e considerate contrarie all’etica della rieducazione.

More, inoltre, propone un modello di tolleranza religiosa che è eccezionale per il suo tempo. L’isola accoglie una varietà di credenze religiose e i conflitti teologici sono risolti attraverso il dialogo e la persuasione piuttosto che la coercizione. Questo pluralismo non solo critica la tendenza dell’Europa coeva di risolvere le differenze religiose attraverso la violenza, ma propone anche un modello di coesistenza pacifica che prefigura le moderne società laiche.

Le proposte di More, pertanto, sebbene idealizzate, fungono da critica alle strutture di potere del suo tempo e offrono spunti ancora rilevanti per le discussioni contemporanee su come costruire società più giuste e equilibrate. Utopia, quindi, non è solo un’opera di critica sociale, ma un manifesto filosofico che interroga i fondamenti stessi della società umana. Sebbene l’isola di Utopia possa apparire come un’ideale irraggiungibile, le questioni che solleva sono di straordinaria attualità. L’opera invita a un esame critico delle strutture di potere e delle disuguaglianze, mostrando come la letteratura possa fungere da catalizzatore per il cambiamento sociale e culturale. La visione di More non offre solo una fuga dall’iniquità, ma una mappa per una rifondazione della società basata su principi di equità e giustizia condivisa.

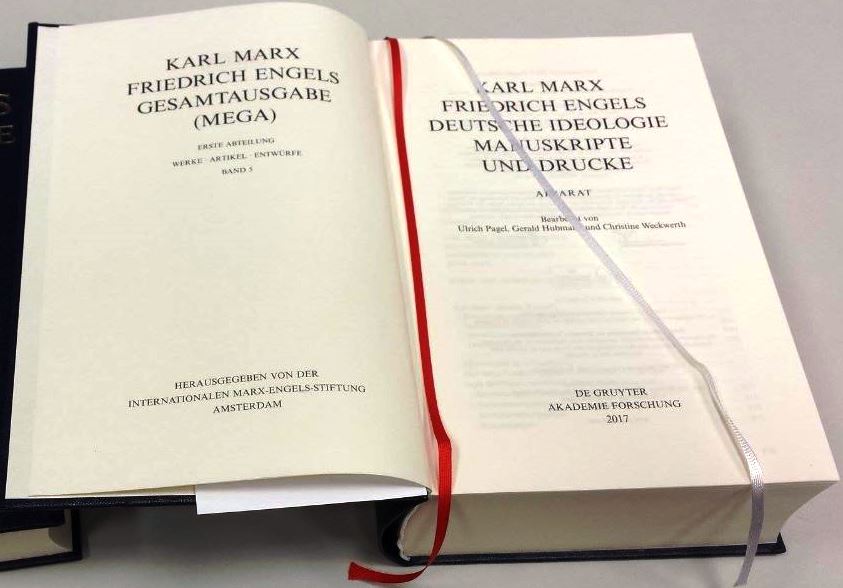

L’ideologia tedesca di Karl Marx, scritta con Friedrich Engels tra il novembre del 1846 e l’agosto del 1846, è un’opera fondamentale nel corpus teorico marxista, essenziale per comprendere l’evoluzione del pensiero del filosofo di Treviri, che lo conduce a una visione più strutturata del materialismo storico. Rimasta pressoché inedita durante la vita degli autori, fu pubblicata postuma solo nel 1932.

L’ideologia tedesca di Karl Marx, scritta con Friedrich Engels tra il novembre del 1846 e l’agosto del 1846, è un’opera fondamentale nel corpus teorico marxista, essenziale per comprendere l’evoluzione del pensiero del filosofo di Treviri, che lo conduce a una visione più strutturata del materialismo storico. Rimasta pressoché inedita durante la vita degli autori, fu pubblicata postuma solo nel 1932.