The Church, so entangled in the life of the Empire that it became a fundamental and constitutive part of it, was also drawn into a lifestyle marked by extravagant luxury and its associated pleasures. Simony and Nicolaitism denounced its moral degradation and spiritual decline, which led it to lose its identity and sense of mission. However, from the second half of the 11th century, spiritualist and ascetic rigorist movements emerged from within the Church itself, even among laypeople, aiming for its transformation and spiritual renewal. These movements sought purity of life and a return to the essential evangelical life modeled after the primitive Church described in the Acts. These movements, characterized by poverty and asceticism, became strong allies of the Gregorian reform and of all the popes who promoted it. However, it must be noted that the spontaneous formation of these groups, often lacking adequate theological and cultural formation and driven mostly by spontaneity and indignation against the Church’s shameful lifestyle, frequently resulted in doctrinally deviant behavior. Nonetheless, these movements, both positively and negatively, were a clear sign that the Church could no longer continue in its current state. They prompted reflection that led to a gradual detachment from the Empire and to a rediscovery of the Church’s identity and mission. Among these, the Waldensians, the Cathars or Albigensians, and the Patarenes are especially noteworthy for their spread.

The Waldensians

They originated from the wealthy merchant Peter Waldo of Lyon. Inspired by a meditation on Matthew 10:5ff, he sold everything he had and embraced the ideal of poverty. His followers were called “Pauperes Christi” (Poor of Christ). His preaching was not without excesses: he criticized the veneration of saints and relics, and also claimed, under pain of sin, that it was necessary to live in evangelical poverty. The bishop forbade him from preaching, but the Third Lateran Council, after he appealed to Pope Alexander III, reinstated his right. However, this permission was revoked by Alexander III’s successor, Lucius III (1181–1185), against whom Waldo rebelled, leading to his excommunication. Waldensianism split into two branches: one in Lyon and one in Lombardy, where followers were persecuted and forced to seek refuge in the valleys of the Turin area, also known as the Waldensian Valleys.

The Cathars or Albigensians

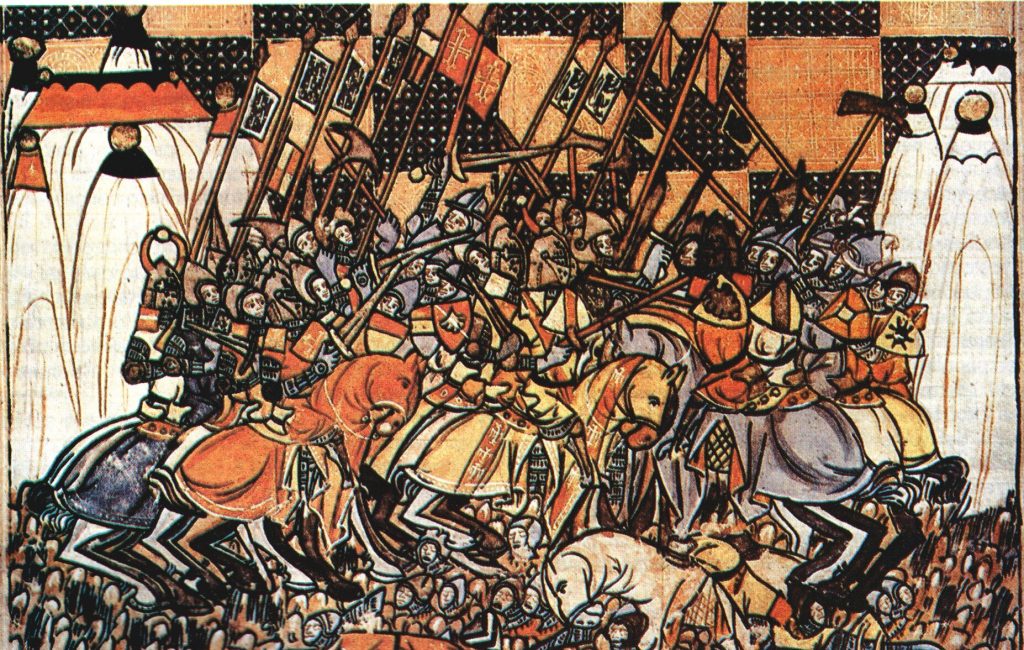

They originated from a form of Manichaeism. They taught that the world was created by the devil, that is, the evil God of the Old Testament, against whom the good God of the New Testament sent his angel Jesus Christ to teach humans how to free themselves from evil matter and thus become pure, or kaqaroi. Consequently, all of creation was seen as evil, including the human body, marriage, and sexual relations — all things to be avoided. They opposed the wealthy Catholic Church with their own poor church, organized similarly to the Catholic structure. The Cathars also fought fiercely against the state, referring to the emperor as the “proconsul of Satan.” They spread mainly in France, particularly in Albi, from which they took the name Albigensians. Their wide reach in France led them to ally with barons preparing for conflicts against the French Crown. Thus, Church and State joined forces to fight them — the former with the Inquisition, the latter with military force. Pope Innocent III (1198–1216) called a crusade against them, which triggered a twenty-year war with massive bloodshed.

The Patarenes

This was a political-religious movement that emerged in Milan around the mid-11th century in opposition to the oppression of the corrupt high clergy. It was composed mainly of the lower classes and was called the Patarenes, named after the Milanese rag market. The movement arose as a reaction to the appointment of Guido da Velate as Archbishop of Milan.

The Inquisition

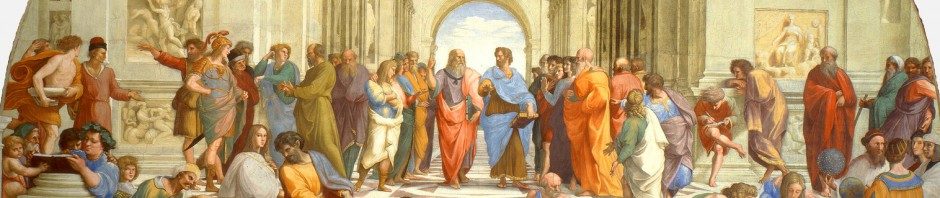

In the Middle Ages, there was strong solidarity between Church and State, which, under Charlemagne and the German Ottonians, became one of identification between religion and politics. Within this framework — where faith was not separate from one’s civic identity — any doctrinal deviation was also considered an attack on the state, due to the deep bond between the two. Heresy was thus not seen merely as doctrinal error, but as opposition to the Church and to the established order. In the context of medieval heresies, a distinction must be made between “heterodoxies” — erroneous opinions developed within academic and intellectual circles and largely confined there — and the popular heretical movements characterized by ascetic rigor and populist biblical interpretations. These movements often represented a distorted and extreme reaction to the Church’s luxurious and indulgent lifestyle. Their goal was a “renovation of the Church,” but pursued in the wrong way. Thus, by opposing the Church, they undermined the harmonious world of the noble Church and, consequently, the social order.

Combating Heresy and the Inquisition

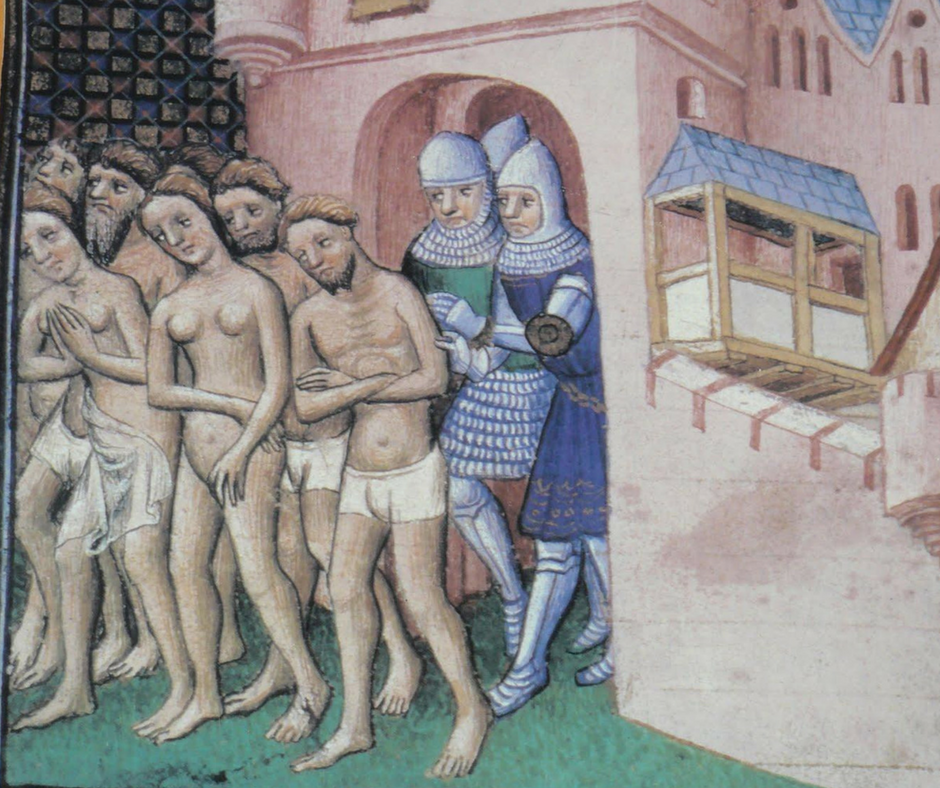

As long as heresy remained sporadic and confined to academic circles — which already had internal mechanisms for repression — or existed among the populace as mere erroneous belief, it posed no major issue. The problem arose when heresy rapidly spread among the people and formed organized movements that often led to uprisings and disturbances of social peace around 1150. This prompted the pope to issue strict measures against heresy, which was classified as a crime of lèse-majesté and disturbance of public order. The fight against heretics thus aimed at safeguarding and restoring social peace and public order. A significant boost to this fight came from procedural reform: judges no longer acted only upon complaints but also conducted official investigations, taking an active role in accusations. This led to the development of the inquisitorial procedure — the Inquisition. In its initial phase, the Inquisition was overseen by individual bishops who appointed “inquisitors,” though they proved largely ineffective. It was under Gregory IX (1227–1241) and Innocent IV (1243–1254) that the Inquisition gained considerable operational and legal momentum: it shifted from an episcopal to a papal institution, and the inquisitors were granted extensive powers, combining the roles of prosecutor, judge, and sentencer. Heresy became a crime under exclusive papal jurisdiction. Trials were held behind closed doors, and the accused were stripped of all rights. The inquisitor typically sought to confirm his own investigations and did not hesitate to resort to torture. In this climate, trials became public spectacles, with verdicts often predetermined. The Inquisition was most established in Italy, Spain, and France. Gregory IX entrusted it to the Dominicans and Franciscans. There were two types of Inquisition: one of papal origin, initiated by Innocent III (1198–1216), and one of Spanish origin, launched by the Spanish monarchs in 1478, which became a tool of royal power against Jewish, Islamic, and heterodox minorities. From a legal perspective, there were two inquisitorial procedures: one ex officio — where papal legates independently sought out heretics — and one based on denunciation. Once heresy was confirmed, the heretic was urged to recant; if not, they were handed over to the secular arm, which usually sentenced them to death, commonly by burning. Under Innocent IV (1243–1254), torture was authorized to extract confessions of heresy. Besides heretics, the Inquisition also targeted witchcraft, another obsession of that era.

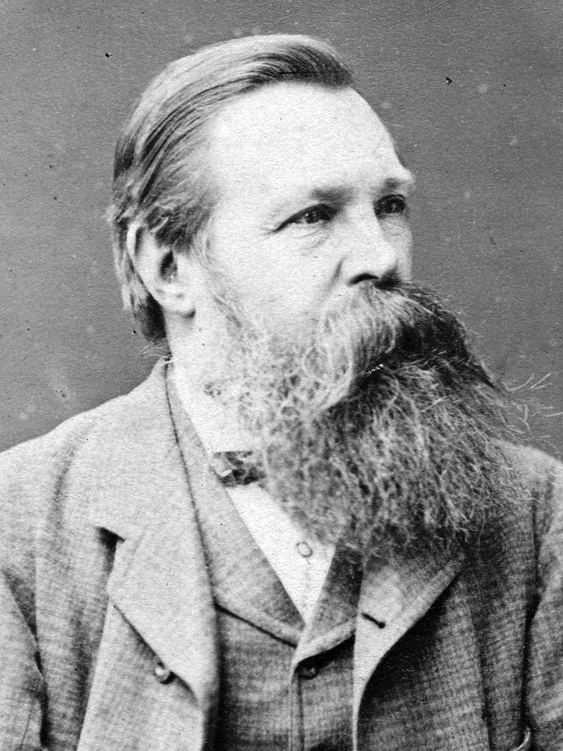

L’idea di La Sacra Famiglia nacque dall’esigenza di rispondere a Bruno Bauer e ai suoi seguaci, che sostenevano una forma di critica idealistica basata su un atteggiamento elitario e intellettuale, senza alcun legame con la realtà materiale e con la lotta delle classi. Marx ed Engels, invece, erano sempre più orientati verso un’analisi materialistica della società e delle sue contraddizioni economiche e politiche.

L’idea di La Sacra Famiglia nacque dall’esigenza di rispondere a Bruno Bauer e ai suoi seguaci, che sostenevano una forma di critica idealistica basata su un atteggiamento elitario e intellettuale, senza alcun legame con la realtà materiale e con la lotta delle classi. Marx ed Engels, invece, erano sempre più orientati verso un’analisi materialistica della società e delle sue contraddizioni economiche e politiche.