These my brand-new reflections on geopolitics present it as a philosophical field, emphasizing the influence of geography on political strategies and the impact of geopolitical actions on collective identities and human conditions. It integrates classical philosophical thoughts on power and State acts, aiming to deepen the understanding of nations’ strategic behaviours and ethical considerations. This reflective approach seeks to enhance insights into global interactions and the shaping of geopolitical landscapes.

The Geo-Philosophy

Part I

Philosophy no longer makes individuals wiser nor does it impart wisdom; it neither aids in making beneficial life decisions nor does it bring happiness. However, it certainly does not leave everything unchanged—it is not a futile endeavour. This can be demonstrated through indirect reasoning, for instance by examining how political power has repeatedly striven to seize it or control its discourse.

Yet, the issue is more intricate and simultaneously more straightforward than it appears. First, because philosophy is not merely prey to the political; and second, because the relationship among philosophy, politics, and history is highly complex. It is only through the interplay of this complexity, resembling the ever-changing patterns of a kaleidoscope, that we can glean insights into the characteristics of our way of life, our culture, traditionally referred to as the “West.”

It is thus possible to begin with the observation that philosophy is a fundamental and essential aspect of the “Western project.”

The need to define this term (“Western project”) necessitates first clarifying what “project” implies here. If by project we mean looking forward, the foresight of what will be done, and the structured plan of a construction, then it can be defined as the plan that allows us to foresee everything that needs to be done to then tackle a specific construction.

In general, the blueprint upon which our way of life was developed and built includes three constructive orders: the organization of coexistence, the continuity of events, and the certification of beliefs. The West is an ongoing construction whose unfolding is articulated as a combination of these three problem-solving constructs. On the plane of coexistence, the Western project unfolds as a state organization; on that of eventuality and its impermanence, it unfolds as History; and on that of belief and its uncertainty, it unfolds as Philosophy. The State organizes the community, History retains events, Philosophy transforms faith into truth.

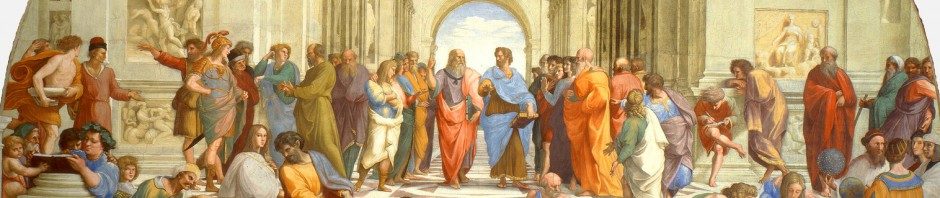

One might wonder in what sense philosophy certifies belief, and the answer is that philosophy arises and establishes itself in opposition to myth. The struggle between philosophy and myth is authoritatively attested by Plato. This struggle is primarily a battle for control over the education system (Paideia) and unfolds in three ways: 1. the exclusion of poets, that is, the wise producers of myths, from the Polis; 2. the repositioning of mythical wisdom in a subordinate role to philosophical knowledge; 3. an unequivocal condemnation of the sophist, that is, the practitioner of a private and thus particularistic Paideia, and moreover in exchange for money.

Philosophy firstly rejects the mere faith-based nature of myth (that which is strongly believed is true) and its inability to establish itself as an exclusive sphere, thereby preemptively invalidating the emergence of other myths, and thus of different and conflicting truths. Philosophy counters the particular knowledge of myth and sophistry with the idea of a universal and incontrovertible knowledge. Now, the philosopher’s certainty of possessing absolutely certain knowledge is based on the acquisition of two notions: 1. truth as unveiling (Alétheia); 2. Being as totality (En-pan). By invoking these two notions, philosophy asserts itself as a total, exclusive faith: philosophy is the eternal and ubiquitous knowledge of the unveiled, that is, of that which, remaining unchangeably in the philosopher’s gaze, is always and everywhere true.

The extent to which this conviction is in turn a belief is something that, following the break from Hegelianism, will be categorically highlighted. Philosophy is no more a certain knowledge than myth was, with the difference that this myth, which is philosophy, has found in the coordination with the State and with History the means to suppress, disqualify, or annihilate any different use of the mind.

State, History, and philosophy are not independent magnitudes. Together, they constitute the response to the problems of the incompatibility of coexistence, the impermanence of events, and the uncertainty of belief, whose kaleidoscopic interplay forms the ever-changing, yet always unified, shape of Western civilization. It could be said that each of these magnitudes presupposes and inevitably refers back to the other two, and that none of the three would have the meaning they do outside of their mutual and triadic relationship, nor could they be separated from this relationship without compromising the entire system’s structure, thereby somehow causing its breakdown. This is a system of transparent planes, each bearing a design; their overlapping, in multiple combinations, gives us the complete design of Western Kultur. What allows the reading of the three planes as a civilization project is thus their very transparency. This system of complex overlays could be termed the Western synthesis, namely the union, the joint capacity for promotion, and the mobile connection of State, History, and Philosophy, along with the transparency of each plane relative to the others.

For instance, knowledge that sought certainty outside the constraints imposed by historical existence would be nothing more than the myth against which Plato fought to establish philosophy as the foundation of all public education. Moreover, if there were no centralized and singular control over the education system, if the Paideia presented itself as a multiplicity of conflicting and irreducible proposals, then there would not be a State, i.e., there would not be a single system of publicity and therefore not even a single system of meaning, there would not be that Einsinningkeit, that unisignificance of facts that is the foundation of the Western mind. In its place, we would have something like a plurality of private meanings and disparate images, and thus the possibility, always given, of their irreconcilable conflict; we would have something powerful, tyrannical, and at the same time inert, flaccid, treacherous, something both superstitious and simultaneously dazzling like a foggy lunar night, like a charming creature yet veiled in damp mists, dim, feverish, internally corrupt and contradictory like Madame Chaucaht.

Thus, the West is primarily a State, that is, the opening of a public space measured by Man, whose measure is Man but only insofar as he is philosophically educated—thus: Homo philosophicus and not “man” simply. The West, following the metaphors of the Magic Mountain, is the “clear day,” the “daylight” where things appear in their incontrovertible objectivity, and “cold,” that is, rational, and finally “glassy,” that is, transparent, unambiguous. This public space, rational, objective, and unambiguous is the realm of manifestation of meaningful events. The meaning of such events, for the philosophically educated being, is univocal, that is, universally comprehensible and transmissible. Such events are thus, so to speak, “eternal facts,” which precisely means: transmissible according to a single meaning. For this reason, they are said to belong to History. History is not the space of facts that simply happen and to which “man” simply conforms, but the realm of the happening of “eternal facts,” which are “facts” only for the Homo politico-philosophicus.