No era ends without announcing the next, and no new era begins without rooting itself in the previous one. This was also the case with the Middle Ages, whose foundations began to take shape in late antiquity.

One of the earliest signs of this transition was the division of the Christian Roman Empire, initiated by Constantine with the transfer of the capital from Rome to Constantinople on May 11th, 313. This division, between the Eastern and Western Empires, became definitive with the death of Theodosius the Great in 395. At the same time, in the 4th and 5th centuries, the popes of Rome began to claim increasing authority in the Church, basing their position on the figure of the apostle Peter. This power, due to the political vacuum left by the emperors who had moved to Constantinople, extended also to the state. Another foundational element was the theology of St. Augustine (354–430), regarded as the father of Western thought.

However, these factors alone would not have been enough to inaugurate a new era without the addition of other decisive events, such as the migrations of Germanic peoples in the 5th and 6th centuries, which led to the fall of the Roman Empire in 476 and the conversion of the Merovingian king of the Franks, Clovis, to Christianity in 498. Another crucial moment was the rise of Muhammad in 622 and the expansion of Islam, which conquered many Mediterranean regions that had once belonged to the Western Empire. The coronation of Charlemagne on Christmas night in the year 800 marked the reestablishment of the Holy Roman Empire, uniting sacred and temporal power, with important consequences for the Church, which, entangled in worldly power, saw a gradual spiritual decline. This led to the famous Investiture Controversy, culminating in the Concordat of Worms on September 23rd, 1122, between Pope Callixtus II and Henry V.

Another crucial moment was the Gregorian Reform of the 11th century, which, under the pontificate of Innocent III (1198–1216), represented the height of the Middle Ages, while already laying the foundations for the crisis of the 14th and 15th centuries and the beginning of a new era: the modern age.

What is meant by Middle Ages?

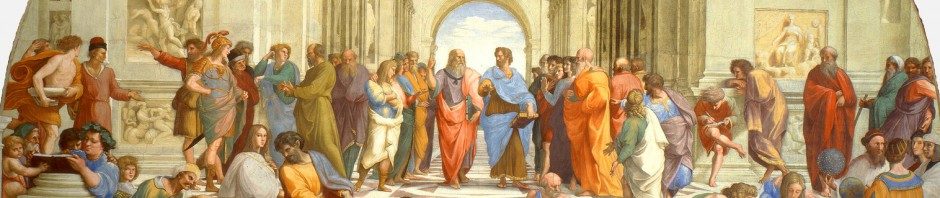

The term Middle Ages refers to the period roughly from 400 to 1500 CE, from late antiquity to Humanism and the Renaissance. This term originated in the 16th century among humanists and was already present in Petrarch (1304–1374). Humanists tended to evaluate this period negatively, viewing it as the end of the classical world, compromised by barbarian invasions. A similar judgment was shared by Protestants during the Reformation, who saw in the Middle Ages the decline of the Church. Enlightenment thinkers also harshly criticized this period, considering it a time when reason was obscured.

However, Romanticism and modern historiography offered a contrasting view, seeing the Middle Ages as a period of the birth of new civilizations and cultures, and the origin of modern Europe. It was not, therefore, a period of darkness, but rather the beginning of a new era: the Western world. During this period, three great civilizations emerged: Byzantine, Islamic, and Germanic, from which arose the three major centers of the East, the West, and the Arab-Islamic world.

Historians generally agree in placing the beginning of the Middle Ages towards the end of the 4th century, with the Germanic migrations, while the 7th century, with the advent of Islam (622), is considered crucial as it marked the division of the world into two great blocs: Christian-Western and Arab-Islamic. Another significant event was the Trullan Council (692), which ended the long-standing controversies over Monophysitism, which had arisen after the Council of Chalcedon (451).

Division of Medieval History

Medieval history can be divided into four main periods:

400–700

This is the period in which the Middle Ages began to take shape, with the interaction between Roman and Germanic cultures, facilitated by the Church’s missionary activity. Despite the baptism of Clovis in 469, it took many years before Christian and Roman values were fully assimilated by the Germanic peoples.

700–1050

During this period, there was greater interaction between Roman and Germanic cultures, leading to the formation of a society with distinctly medieval characteristics. It was the era of Boniface and Charlemagne, who laid the foundations of the West by uniting Church and State. In this context, the Church became intertwined with territorial power, and the king assumed a sacred role, influencing ecclesiastical affairs.

1050–1300

This period was marked by strong conflicts between the Papacy and the Empire, such as those between Henry IV and Gregory VII, and between Frederick Barbarossa and Alexander III. Innocent III made the papacy the central authority of the Western Christian world, but it was also the time of the Crusades and the flourishing of universities and Romanesque and Gothic art.

1300–1500

The struggles between the Papacy and the Empire deeply weakened both institutions, paving the way for a new era. The rise of national states and the growing autonomy of the laity prepared the ground for the Protestant Reformation and the end of the Middle Ages.

Characteristics of the Middle Ages

The Middle Ages were defined by a series of distinctive features: (1) the unanimous belief in a unique bond between God and humanity, with a single moral code shared and recognized by all; (2) a close symbiosis between State and Church, between Papacy and Empire, which shaped the unity of the Western world; (3) A rigid division of social classes, considered an expression of divine will, with feudalism at the center of this order; (4) until the 13th century, culture was monopolized by the Church, and only at the end of the Middle Ages did the laity gain greater cultural autonomy.

Thus, the Middle Ages were a period of great transformations, in which new civilizations emerged, laying the groundwork for the modern world.