Despite the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the decline of the Church, which had leaned heavily on the Empire, the West did not disintegrate. Instead, it completed its geographical and political configuration by integrating the northern regions into Christianity. Two factors contributed to the revival of the West: Christian culture and religion, which became a unifying cultural amalgam upon which a new unifying political framework was built; Otto I of Germany, who saw himself as the natural heir of Charlemagne. Crowned in Aachen in 936, Otto undertook the restoration of the fragmented Empire and the fallen Church, initiating sweeping reforms that revitalized both institutions.

Internal and External Policies of Otto I

In domestic politics, Otto I diminished the power of dukes and counts by granting public rights to bishops and abbots. He reserved the right to appoint bishops, making them pillars upon which the Kingdom of Germany rested. In foreign affairs, Otto I descended into Italy in 951 to free Adelaide from Berengar II and marry her. During this campaign, he assumed the title of King of Italy in Pavia. Subsequently, Pope John XII (955–963) sought Otto’s help against Berengar II. In 962, Otto was crowned emperor and recognized as such. On this occasion, he granted the papacy the “Privilegium Ottonianum,” reaffirming the ecclesiastical privileges from Charlemagne’s era and requiring newly elected popes to swear loyalty to the Emperor. However, John XII’s intrigues led Otto to limit papal autonomy, decreeing that no pope could be elected without his consent. John XII was deposed, and Leo VIII was elected in his place. While the papacy lost its autonomy under Otto I, this reform rescued it from the dark crisis of the “Saeculum Obscurum” (the Dark Age).

In domestic politics, Otto I diminished the power of dukes and counts by granting public rights to bishops and abbots. He reserved the right to appoint bishops, making them pillars upon which the Kingdom of Germany rested. In foreign affairs, Otto I descended into Italy in 951 to free Adelaide from Berengar II and marry her. During this campaign, he assumed the title of King of Italy in Pavia. Subsequently, Pope John XII (955–963) sought Otto’s help against Berengar II. In 962, Otto was crowned emperor and recognized as such. On this occasion, he granted the papacy the “Privilegium Ottonianum,” reaffirming the ecclesiastical privileges from Charlemagne’s era and requiring newly elected popes to swear loyalty to the Emperor. However, John XII’s intrigues led Otto to limit papal autonomy, decreeing that no pope could be elected without his consent. John XII was deposed, and Leo VIII was elected in his place. While the papacy lost its autonomy under Otto I, this reform rescued it from the dark crisis of the “Saeculum Obscurum” (the Dark Age).

Otto I’s Imperial Ideology and Claim to the Crown

By being crowned in Aachen in 936, Otto I considered himself the rightful heir of Charlemagne and the Holy Roman Empire. Although German kings traditionally governed their realms without overstepping their borders, Otto I embraced Charlemagne’s sense of “dignitas imperialis,” which made him feel responsible for the entire Western Christendom. He regarded imperial consecration and coronation as a sacrament, binding him closely to the Church and involving him in its priestly mission. Otto consistently felt personally responsible for the papacy and the Church, grounding his politico-religious vision of the Empire in this conviction. Under Otto I, State and Church were not only deeply united but nearly merged into a single identity. Over time, the imperial perspective evolved to assert a direct right to the crown, viewing papal acknowledgment as mere formality. However, this view clashed with the Roman stance, which maintained that the pope’s blessing and consecration were essential. This debate resurfaced in the 11th century during a dispute between Frederick Barbarossa and Pope Adrian IV. The pope demanded gratitude for his imperial investiture, while Barbarossa argued that his election by German princes was divinely sanctioned, rendering papal acknowledgment redundant. Thus, the theological-political question arose: did imperial authority derive directly from God or through the pope? Two factions emerged: canonists advocating papal mediation and those asserting that God directly conferred authority through the election by German princes, leaving the pope to merely recognize the outcome. The issue was resolved under Pope Gregory VII (1073–1085), who, in his Dictatus Papae (1075), claimed the right to examine and approve the emperor’s dignity.

Temporal and Spiritual Power in the Early and High Middle Ages

Why did such theological and legal disputes arise? Were they merely about power struggles? The answer lies in the theological and religious worldview that guided the Church, Empire, and medieval society. From Charlemagne to Henry III, imperial power increasingly permeated the Church, not as an intrusion but as a rightful involvement in matters of shared concern. Imperial sovereignty was conferred not only through political election but also through sacramental consecration. Consequently, kings wielded sacred authority (Sacra Potestas Regalis), enabling them to intervene in ecclesiastical affairs alongside the clergy. Two elements defined this Sacra Potestas Regalis: Political religiosity – everything religious was public, and everything public was also religious; The concept of the “proprietary church” – every power regarded itself as sacred, thus bearing responsibility for the “holy things” (res sacrae). These principles significantly shaped the idea of royal authority.

The King’s Role in the Church

Given the king’s sacredness within the Church, how did royal authority (potestas regalis) relate to papal authority (auctoritas pontificalis)? Two complementary theories addressed this relationship: Theocratic Monism – this held the supremacy of kingship over the priesthood. Based on Christology, it argued that Christ’s eternal kingship preceded his priesthood, which later emerged to mediate between God and humanity. The king, as Christ’s representative, embodied divine sovereignty; Theocratic Dualism – based on the “two swords” theory (Luke 22:38), it symbolized the temporal and spiritual powers, both derived from God with the shared goal of maintaining justice and order. While the monarchy defended and propagated faith, the priesthood sanctified and redeemed. Yet, given the monarchy’s means of wielding power, it often assumed supremacy over the priesthood, reverting to theocratic monism.

The Culture of the King’s Church

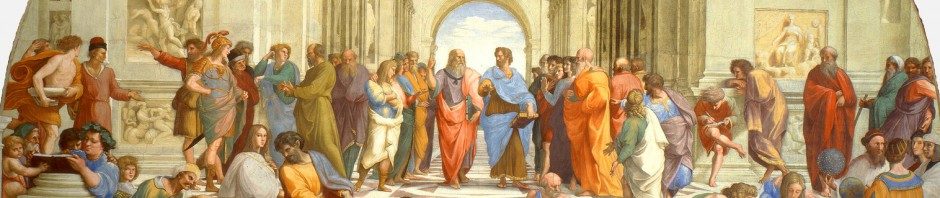

Within this theocratic framework, art and culture were entrusted to the Church, with rulers acting as patrons. Cultural production reflected the splendor of royal power as an extension of Christ’s glory (splendor Christi), while the king’s authority was seen as participation in Christ’s rule. This harmony between Kingship and Priesthood extended to the social harmony between the powerful and the poor. Ecclesiastical institutions, especially monasteries, undertook social and charitable responsibilities, emphasizing the duty of the powerful toward the weak.

Concept of the “Proprietary Church”

Emerging from late antiquity (4th–5th centuries), societal reforms transformed property owners into local sovereigns, exercising authority over people and resources on their estates. This signoria fondiaria encompassed territorial sovereignty over both secular and ecclesiastical domains. Churches, monasteries, clergy, and religious institutions fell under the jurisdiction of landowners, who maintained both administrative and spiritual oversight. During the Carolingian era, laws required landowners to allocate parts of their estates to the Church. While these allocations became investments in the “proprietary church,” landowners retained their authority over the properties and ecclesiastical personnel.

The “Domus Episcopalis” and its Evolution

The Domus Episcopalis represented the bishop’s administrative and pastoral authority, encompassing ecclesiastical resources, oversight of the clergy, and care for the laity. As the Church expanded, bishops decentralized spiritual care, establishing centers with “episcopal rights.” Over time, these centers gained autonomy, creating parishes with independent assets while remaining spiritually tied to the bishop. By the 11th century, the Domus Episcopalis had dissolved entirely. Bishops, increasingly involved in secular affairs, adopted aristocratic roles, culminating in a new archetype, particularly in Germany: bishops as city lords, rulers of proprietary churches, and wielders of royal sovereignty.