After Pope Gregory VII asserted the “libertas ecclesiae,” which reached its peak under Innocent III, the task of spreading and affirming the faith (negotium fidei) fell entirely to the Church, which became its primary advocate. Among these efforts were both the Crusades and the struggles against heretics. This movement followed a precise logic: the Church’s spiritual authority (gladius spiritualis) issued decrees and bulls (gladius spiritualis materialis) that justified certain undertakings, which were then entrusted to the king (gladius temporalis). This framework operated within a historical and social order perceived as divine, ordained by God for salvific purposes.

Formation and Motivation of the Crusading Idea

The Crusades, launched to liberate the Holy Land from Islam, were based on two fundamental principles: a religious-political one—the “pilgrimage to Jerusalem” and the “libertas ecclesiae”—and a practical one: removing obstacles imposed by Muslims on the numerous pilgrims traveling to the Holy Land. The Crusades were preceded by armed escorts accompanying pilgrims, thereby integrating into the concept of an armed pilgrimage. They also found their political foundation in the Gregorian Reform’s Libertas ecclesiae: the pope was now responsible for ensuring the Church’s security by liberating it not only from heretics, simoniacs, and Nicolaitans but also from infidels besieging Jerusalem, perceived as an extension of the Church itself. Thus, the early Crusades became a political exercise of the new libertas ecclesiae, shaping the reformed Church of the Gregorian era. Furthermore, while the Church had always maintained a passive stance toward wars, between the 10th and 11th centuries, it was compelled to take a stand against the daily misfortunes, abuses, violence, and feuds plaguing Christian Europe. Particularly in southern France, two “pacifist” movements emerged: the “Peace of God” and the “Truce of God,” the latter appearing at the Council of Elne in 1027, which established specific periods during which violence was prohibited.

However, these pacifist efforts yielded little success. Consequently, security measures led by bishops were implemented to suppress violence and enforce the truces. The knight was entrusted with defending the weak, forming the ideal of the Christian knight. In the latter half of the 11th century, the reforming papacy sought to influence the nobility’s ethics, adopting the instrument of holy war. Gregory VII, who exhibited a strong warrior spirit, inspired the Militia Sancti Petri and linked pilgrimages to the Holy Land with the Church’s freedom. These developments fostered the Church’s concept of Holy War—war waged for religious purposes and in the Church’s and Christendom’s interest, where the use of arms and violence was deemed meritorious if for just causes. Thus, both the defense of the Church and the pilgrimage to Jerusalem were considered acts of merit for the remission of sins. From this sacralization of war emerged the belief that its jurisdiction belonged to the clergy. It was the pope’s prerogative to declare wars “just,” granting indulgences and remission of sins while justifying the violence committed by participants.

To fully understand the phenomenon of the Crusades, one must consider the spiritual climate of Christianitas in the West, shaped by the Gregorian Reform. Only within a Christendom imbued with a strong religious and faith-driven ideal could the psychological, moral, and spiritual conditions enabling the Crusades arise.

The Crusading idea was closely linked to the concept of pilgrimage to the Holy Land, viewed as a return to the cradle of faith and Christianity. The Crusades were fundamentally religious in nature and were conceived as military actions to ensure safe passage and Christian presence in the Holy Places. Additionally, historical circumstances played a role: Rome was deeply concerned about the East’s situation following the Byzantine defeat at Manzikert in 1071 and the Turkish conquest of Jerusalem and Damascus in 1076. What would happen to the West and Christendom if the Eastern Roman Empire collapsed? Another crucial factor in the formation of the Crusades was chivalry. After the Carolingian Empire’s dissolution, chivalry became synonymous with plunder, robbery, and oppression. The Church’s patient educational efforts redirected these energies toward noble ideals of protecting the weak and women. Finally, through a liturgical consecration, the knight took on the form of a Christian warrior, akin to a religious soldier. Nobility began to converge within the chivalric ranks, leading to the rise of knightly orders, which the pope would later call upon to defend Christendom and the Holy Sepulcher.

The Crusades: Historical Aspects

There is no doubt that the ideals driving the Crusades were primarily Christian and missionary in nature. What prompted the pope and Western Christendom to create these military movements for conquest and liberation was the alarming situation in the East: the Turkish conquest of Jerusalem (1071) and the continuous complaints from pilgrims about Turkish oppression. Additionally, Islamic armies threatened Constantinople, leading Emperor Alexios I to seek Western aid. Pope Urban II, moved by these appeals, made a passionate call to Christendom at the Synods of Piacenza and Clermont. The response was overwhelming, with the unanimous cry of Deus lo vult! as Europe mobilized to aid the Byzantine East and liberate the Holy Land. Since both Henry IV and Philip I were excommunicated, leadership of this vast movement fell to the pope. Remarkably, this happened just 50 years after the Synod of Sutri (1046), in which Henry III had saved the papacy and set it on the path to universal greatness.

The Major Crusades

First Crusade (1096–1099)

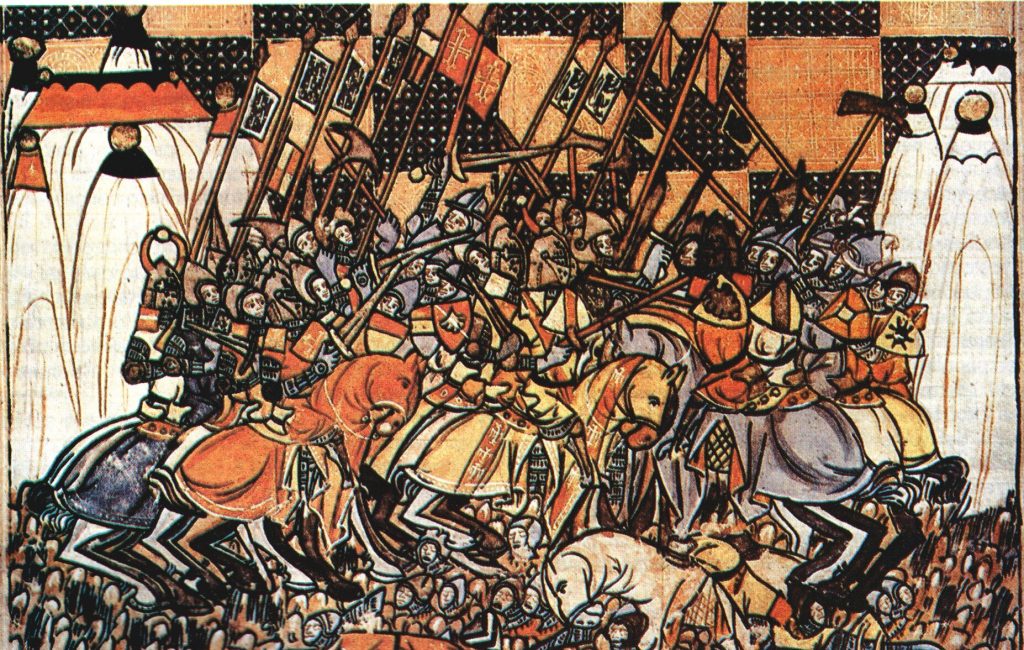

Urban II’s powerful speech at Clermont, spread by zealous preachers across Europe, ignited fervor. The popular response was overwhelming. An enormous crowd of peasants and commoners, led by Peter the Hermit, preceded the official crusading armies. However, these undisciplined zealots committed bloody massacres of Jews and engaged in pillaging and violence along their path. They were swiftly annihilated by the Turks in their first encounter. The main army, divided into four contingents, converged at Constantinople in 1097 and, in July 1099, conquered Jerusalem, unleashing disgraceful looting and horrific massacres of the local population. The outcome of this First Crusade was the establishment of the Christian Kingdom of Jerusalem, modeled on the feudal system with small principalities.

Second Crusade (1147–1149)

Launched to aid Eastern Christians against the Turks, who had seized Edessa (1144). Preached fervently by Bernard of Clairvaux, the crusading armies of France and Germany regrouped but suffered heavy losses, ultimately returning defeated and disillusioned. This left the Kingdom of Jerusalem isolated and vulnerable to the powerful Saladin, who conquered it in 1187. This set the stage for the Third Crusade.

Third Crusade (1189–1192)

Responding to Saladin’s conquest of Jerusalem, this well-organized crusade achieved a brilliant victory at Iconium. However, the unexpected death of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa deprived the expedition of its leader, preventing further success. Nonetheless, it secured a truce allowing Christians access to Jerusalem.

Fourth Crusade (1202–1204)

The death of Saladin (1192) encouraged the West to embark on another crusade, promoted by Pope Innocent III. Unfortunately, the expedition, financed by Venice, which had expansionist and commercial ambitions in the East, was diverted to Constantinople. There, after a horrific massacre that deepened the rift between East and West, the Latin Empire was established, provoking bitterness and outrage throughout the Western world. This crusade was a religious and political tragedy to the extent that doubts arose about the feasibility of continuing these “Christian expeditions.” It was at this point that the idea emerged that God might prefer to rely on defenseless virgins and children rather than warriors. Inspired by this notion, the so-called “Children’s Crusade” (1212) took place, consisting of boys from France and Germany, but it ended in utter failure.

Fifth Crusade (1217–1221)

This was a private enterprise undertaken by the excommunicated Emperor Frederick II, which ultimately proved to be a substantial failure. The crusaders seized Damietta in Egypt with the intention of exchanging it for Jerusalem; however, they became trapped there and were forced to retreat hastily to save themselves. It was in Damietta, in 1219, that Saint Francis attempted, unsuccessfully, to convert Sultan Al-Kamil.

Sixth Crusade (1228–1229)

This was the only crusade, aside from the First, to achieve positive results. Led by Frederick II, it secured Jerusalem, Nazareth, and Bethlehem through negotiations with Sultan Al-Kamil, along with a ten-year truce. However, Christendom viewed this achievement with suspicion, considering it impious, though Jerusalem remained under Christian control until 1244.

Seventh Crusade (1249–1254)

King Louis IX took on the mission of liberating the Holy Land, but after conquering Damietta, he was captured and remained imprisoned for four years before returning to France upon paying a hefty ransom. He later attempted an Eighth Crusade (1270), which ended in disaster as disease decimated his forces. The king died in front of Tunis. Twenty years later, all Latin possessions in the East were abandoned.

The Consequences of the Crusades

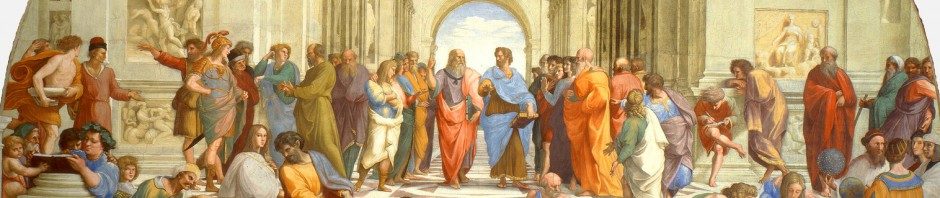

Although the Crusades ultimately ended in military failure, they had a profound impact on social, cultural, political, and religious spheres. For nearly two centuries (1095–1291), Europe rediscovered its Christianitas, rallying around the papacy as the spiritual, religious, and political leader of the West, transcending the boundaries of individual states. During these centuries, a unified European and Western consciousness emerged, with the papacy serving as its focal point and unifying force. Additionally, there was a spiritual and religious awakening of consciences, as people viewed the Crusades as a Peregrinatio religiosa—a sacred pilgrimage modeled on the poor and crucified Redeemer, inspiring the ideal of imitating Christ through poverty and penance. This, in turn, led to the rise of the first pauperist movements. Another consequence was the increase in the religious and political authority of the papacy, which became the central force unifying all of Western Christendom. The Crusades also fostered a renewed connection between the West and the East, akin to a return to Christian origins. They facilitated encounters with Arab culture, particularly Arab-Aristotelian philosophy, opening new theological perspectives. Trade also benefited, especially for Venice, which built its commercial empire upon the Crusades. Finally, the Crusades alleviated social tensions by channeling everyday violence into what was perceived as a righteous cause. For violent individuals, troublemakers, impoverished wanderers, and adventurers, the Crusades provided an outlet for their existential instability.

Negative Aspects of the Crusades

The Crusades’ results were meager, disappointing, and virtually nonexistent. The objectives set out were largely unfulfilled, leading to massive casualties and unimaginable violence that wounded the consciences of both the Western and Eastern worlds. From an evangelical perspective, the Crusades were a disaster, inflicting a deep spiritual and moral wound within the Church. In recent times, the Church has felt the need to seek God’s forgiveness for the immense, reckless massacres and the great suffering inflicted on a part of humanity.